Main points:

– The cooperation of the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation is crucial in countering hybrid threats and should be a priority within the framework of ongoing security cooperation;

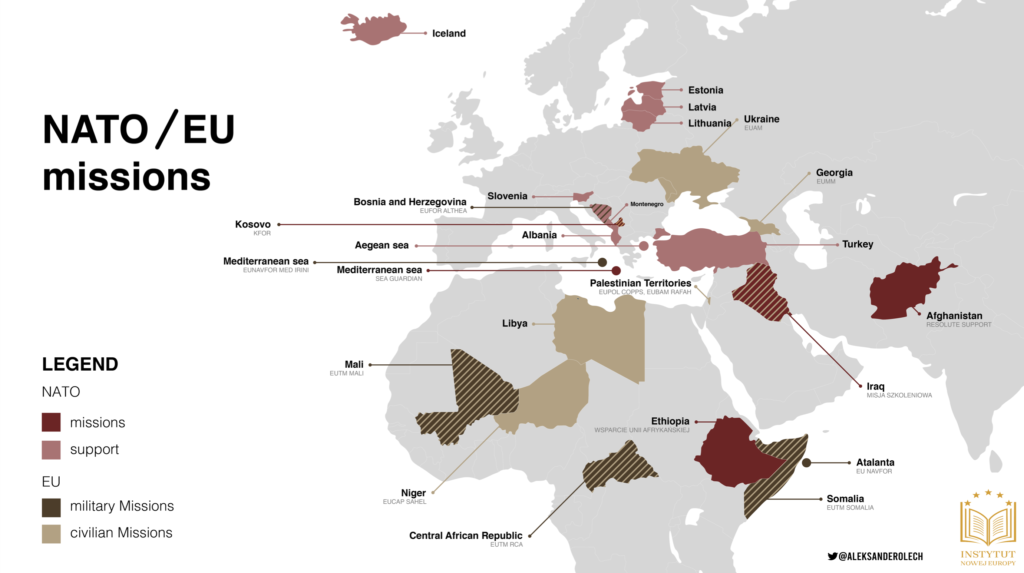

– Undertaking joint international missions will effectively strengthen the cooperation in counterterrorism operations, including those outside Europe;

– It is important that NATO and EU missions are carried out in the wider agreement and as part of a joint effort, especially in the Central and North Africa region;

– The EU and NATO have the instruments to conduct a common policy related to security and defence, especially when it comes to the NATO’s Eastern flank in Europe.

Preface

Nowadays, NATO and the EU have similar interests and face the same challenges regarding crisis management cooperation, as well as military, political and economic capacity development and support for common partners in Eastern and Southern Europe. Relations between NATO and the EU were institutionalised at the beginning of the 21stcentury on the basis of measures taken in the 1990s to promote greater European responsibility in terms of defence. In this respect, the 2002 NATO-EU Declaration on European Security and Defence Policy, ensuring cooperation in terms of NATO planning and EU military operations, was of crucial importance. It was followed by a strategic partnership established in 2010 and a common concept of actions in the face of challenges in regions of high tension and conflict, which also included combating hybrid threats, was outlined in 2016. In 2018, in a joint declaration both organisations agreed that they would focus on rapid progress in developing military mobility and combating terrorism, as well as chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats. It was also decided to make a joint effort to develop European combat capabilities.

The scope of the fight of the EU and NATO against hybrid threats has covered quite an extensive ground: from the fight against disinformation campaigns to identification and prevention of crises or conflicts (including those of an armed nature). Eventually in 2018, the Council of the EU and the North Atlantic Council approved a joint set of 74 specific security actions, with as many as 20 of them concentrating over the struggle against hybrid threats.[1]

In recent years, difficult relations with the Russian Federation and instability in the Mediterranean Sea, in the form of an influx of migrants, conflicts in North Africa, and a dispute between Greece and Turkey, have posed new challenges to the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Both organisations have begun to place a greater emphasis on combating hybrid threats, strengthening regional defence and countering terrorism. In the course of this development, both the EU and NATO have deepened their cooperation, seeking to harmonise their political and strategic objectives.

In the current environment, faced with both old and new challenges, a cooperation between the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation remains of substantial importance. The security of EU and NATO are interconnected, making member states work together and make efficient use of the wide range of tools and resources available to answer the challenges and increase security of their citizens. The EU-NATO cooperation constitutes an integral pillar of the EU’s effort to strengthen European security and defence capabilities. The partnership between the two organisations strengthens the transatlantic link and the EU’s defence initiatives contribute to an even military engagement in Europe with the help of NATO forces. In other words, stronger EU and a stronger NATO reinforce one another.

There are currently eight key areas to advance within the cooperation between the EU and NATO:

1. Counteracting hybrid threats,

2. Operational cooperation – especially at sea, in the face of an increased migration,

3. Cyberspace security,

4. Defence capabilities,

5. Arms industry,

6. Scientific research on security, technology and military issues.

7. Joint exercises and training,

8. Support for the allied countries in the east and south of Europe in the framework of partnership.

The cooperation is based on the already established norms and good practices, guided by the principles of openness, transparency, communication and reciprocity, while fully respecting the decision-making autonomy and procedures of both organisations and maintaining the nature of the security and defence policy of the individual member states.

Hybrid threats

Hybrid threats and therefore conducted hybrid actions are understood as a combination of regular and irregular actions (i.e. of varying intensity and frequency), both undertaken by armed forces as well as criminals, terrorists, or even political organisations. Such new form of threat, or rather its diverse nature, indicates the need to verify the ability of states to respond to perils of this kind. This is primarily related to actions of governments, efficiency of defence systems, and international security cooperation in terms of security. In this case, it is crucial to view the current situation in Ukraine, the Balkans, Syria, Libya, or Central Africa through the prism of both military and non-military challenges.

It should be noted that the costs of conducting irregular attacks described as hybrid actions are much lower than those of traditional war. Moreover, the attacker is not, at least not entirely, exposed to a strong reaction of international community. The hybrid conflict in Ukraine is part of an evolution that is taking place in post-Soviet countries (as is currently happening in Belarus, for example). It is a multidimensional crisis, comprising the actions of national and supranational entities pursuing their political and economic interests with the available range of methods: from the conventional use of armed forces to fake news distribution. Allowing the development of separatist enclaves, such as those in Moldova, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, is a serious problem and requires these countries to cooperate with NATO and EU member states and create a common sphere of security.

European Union defined hybrid threats as a mixture of coercive and subversive activity, as well as conventional and unconventional methods (i.e., diplomatic, military, economic, technological), which can be used in a coordinated manner by state or non-state actors to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the thresh-old of formally declared warfare.

NATO’s perception of hybrid threats & warfare is that of a violent conflict that features the simultaneous application of conventional and irregular warfare tactics, that can involve both state or non-state actors, which are used fluidly while disregarding the limitations of a physical battlefield or territory. Each attack contains its own combi-nations of the two and targets aspects of state and society as a means of achieving one’s own objectives. The nature and tools required to wage hybrid warfare do not discriminate between state or non-state actors, with non-state actors (such as ex-tremist groups) being equally able to wage this kind of warfare in equal measure as a state actor and its military forces can.

Strengthening NATO-EU cooperation

As hybrid threats exploit the synergy of different actors and activities, this very fact should be taken into account in the planning of defence mechanisms. In order for all actors to head for the same goal, a common understanding of hybrid risks is needed. At an international level, civilian and military personnel of NATO and EU institutions carry out the fight against it. Therefore, in order to ensure cooperation between NATO and the EU, the European Commission and the European External Action Service have set up an inter-ministerial group on hybrid threats, which meets regularly to maintain the European institutions’ processes for dealing with hybrid threats. The priority is to organise regular training and exercises on combating hybrid risks.

Since 2016, NATO and the European Union have defined hybrid threats as one of the greatest challenges they have been facing. Therefore, in 2017, the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE) was established in Helsinki, which plays a significant role in facilitating such cooperation. Hybrid CoE focuses on responding to hybrid threats and exchanging best practices between European Union and NATO services.

Furthermore, a constant development of the European Union’s security and defence policy should be highlighted. Its important element was the establishment of a permanent, structured cooperation (PESCO) in the field of defence between EU members in 2017. The initiative involves enhanced cooperation between the selected countries aimed at joint planning, developing, strengthening, and investing in defence capabilities. The main objective is to develop capabilities of international nature in the implementation of EU, NATO, and UN missions. Together with the Coordinated Annual Defence Review (CARD), the European Defence Fund (EDF), and the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC), a comprehensive defence package for the EU has been created.

One of NATO’s most important objectives is to create a stable defence wall on the eastern flank of the alliance, which at the same time constitutes the eastern border of the EU. However, there are differences in the perception of threats by individual states. Countries such as Germany, France, and Italy want the EU to be able to react independently to future crises in southern Europe. Poland and the Baltic States, on the other hand, are well aware of a possible threat from the East and support the NATO’s main objective, which is to build deterrents at the EU’s eastern border. It is therefore necessary to analyse these different approaches to the implementation of the PESCO projects and then execute them in cooperation with NATO. Hybrid threats evolve and take on different forms from one region to another, thus it is necessary to constantly adapt new strategies to properly deal with them.

International missions of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union

As the threat must first be fought beyond national or regional borders, international missions are crucial to maintaining security. The actions of the European Union and NATO are complementary and make it possible to verify dangers at an early stage. Due to the diverse nature of hybrid threats, the common strategy of the two organisations brings together foreign policy and strengthens regionally-built alliances. The greatest threat appears to be the hybrid activities carried out by the Russian Federation, its allied separatists and terrorist organisations.

Combining NATO’s military capabilities with the political and economic potential of the European Union is a project that can fully ensure Europe’s security and also play a significant role in the Middle East and Africa. This is due to the different natures of the two organisations and the multinational commitments which their individual members have undertaken. As indicated earlier, the essence of hybrid threats requires an immediate and collective response, and this can only be achieved with a substantial involvement of many actors. Here, international military missions deserve special attention. Both the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union are carrying out a number of activities in the countries where their presence is essential for maintaining order and security. Thus, taking into account the two types of military missions – those carried out by both NATO and the EU – it is possible to counter threats at the same time. The forces and resources of the two international organisations greatly differ and therefore can be used to complement each other’s capabilities and ultimately eliminate hybrid threats. These operations are also of great importance in terms of communications. They play a key role in fighting against disinformation and in verifying the reliability of the information in the networks related to the true state of affairs in conflict regions.

Due to the international nature of hybrid threats, including terrorism, it is important to emphasise the role of civilian and military missions. The foreign activity of the coalition of states allows for combating threats at the place of their origin. Global cooperation of members of both organisations is crucial in effectively responding to oncoming dangers from the Middle East and Africa. Moreover, European countries are responsible for improving the inter-state system of security in order to stop the negative impact of hybrid warfare, disinformation, and terrorism, which occurs in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. For this reason, joint missions are an inevitable element of further cooperation between NATO and the European Union. Only if those two cooperate it will be possible to more successfully combat threats and minimise the risk of their spreading.

NATO missions

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s current missions include[2]:

– Resolute Support in Afghanistan – it provides training, advice, and assistance to Afghan security forces and institutions. The legal basis for the Resolute Support Mission is the formal invitation from the Afghan Government and the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between NATO and Afghanistan, which regulates the presence of allied forces.

– Kosovo (KFOR) – currently there are approximately 3,500 of NATO’s allied troops stationed in Kosovo. The mission started as early as June 1999, with the purpose of ending the ongoing war and stopping a humanitarian disaster. Following Kosovo’s declaration of independence in February 2008, NATO agreed to maintain a military presence under UN Security Council Resolution 1244. Furthermore, NATO strongly supports the European Union in facilitating a dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina. The normalisation of relations between Serbia and Kosovo is key to resolving the political deadlock in northern Kosovo.

– Securing the Mediterranean Sea ‘Sea Guardian’ – a mission carried out on the Mediterranean Sea in order to maintain security, fight counter-terrorism, build defence capabilities in the region, protect freedom of navigation and critical infrastructure, and help maintain cooperative security with other actors in the region. Operation Sea Guardian was transformed from the anti-terrorist operation Active Endeavour during the NATO summit in Warsaw in 2016.

– Training mission in Iraq – formally inaugurated at the summit in Brussels in July 2018 at the request of the Iraqi government to fight the terrorist organisation Islamic State (ISIS). It is a training mission with the main task of building Iraqi forces’ capacity and protecting the region from renewed wave of terrorist attacks. The training concentrates on the following areas: counteracting the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), civil and military planning, armoured vehicle maintenance, and military medicine. NATO also supports building international cooperation with the Iraqi armed forces.

– Support to the African Union – by providing assistance to the mission in Somalia (AMISOM) using air and sea forces. NATO also supports building security capacity and training for the African Standby Force (ASF). The African Union aims to have a high readiness continental security apparatus that would be similar in its operation to the NATO Response Force. It should be stressed that NATO supports the African Union far beyond the Euro-Atlantic region in its peace efforts on the continent. Troops are stationed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

– NATO Air Policing – since the Russian Federation’s illegal military intervention in Ukraine in 2014, NATO has regularly introduced further security measures. One of them has been strengthening of NATO’s air patrol missions. They are peacetime tasks which make it possible to detect, track and identify any violations of airspace and respond to threats. The airspace of the allied countries is patrolled with the use of fighters. In addition, to strengthen the effectiveness of the mission, NATO has deployed additional aircraft over Albania, Montenegro, and Slovenia, as well as the Baltic region, where F-16 or B-52 have repeatedly intercepted Russian aircraft violating the airspace of NATO Member States.

EU missions

The missions led by the European Union are comprised of military and civilian types. However, their nature and area of implementation have great importance. In view of the many hot spots in the world with international conflicts and crises in place, the presence of representatives of international structures is essential. Activities are executed under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), providing the European Union with an operational capability based on civilian and military methods and means.

Among the military missions, the following are worth distinguishing:

– EUFOR Althea – relies on supporting and training of the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina and contributes to creating a secure environment in the country. The long-term political objective of the mission is to create a stable and multi-ethnic state, which cooperates in a peaceful manner with its neighbours and ultimately becomes an EU member. The mission also supports the country in its efforts to join NATO.

– EUTM Mali – a multinational military and training mission of the European Union. Its main objective is to restore long-lasting peace in Mali, essential for long-term stability in the Sahel region and more broadly for Africa and Europe. The mission involves 22 EU members and 6 non-EU countries.

– EUTM CAR – a mission to the Central African Republic is part of the European Union’s broader engagement (covering political, economic, development and security assistance) in response to the crisis in the African country. The EUTM CAR seeks to modernise the Central African Armed Forces (CAAF) and provide strategic advice to the Ministry of Defence and officials of the Central African Republic, as well as educate military representatives.

– EU Naval Force, or Operation Atalanta – the European Union, concerned about the consequences of piracy and armed robbery in the Somali Peninsula region and the Indian Ocean, has launched a sea-air fleet as part of the European Common Security and Defence Policy. These actions contribute to the protection of ships at sea off the coast of Somalia.

– EUTM Somalia – training and advisory activities aimed at developing stability, prosperity and security in Somalia.

– EUNAVFOR MED ‘Irini’ – the European Union has made an effort to enforce the UN arms embargo against Libya. It is thus contributing to peace process in that country by conducting a military operation in the Mediterranean. The operations are carried out using air, satellite and naval resources in cooperation with European Union’s member states.

In addition, the European Union’s civilian missions are also carried out in Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Kosovo, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Niger, the Central African Republic, Somalia, and Palestine.

Another aspect that deserves attention is the fact that 20 countries are both members of the European Union and NATO. At the same time, countries such as Albania, Canada, Iceland, Montenegro, Norway, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States are members of NATO, but not of the EU. Simultaneously, countries such as Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden are members of the EU, but not of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Therefore, using the potential of countries that are not members of one of the two organisations is of importance when planning international operations. Simultaneous and permanent cooperation to strengthen security, defence capabilities and combat capability is possible with the involvement of all countries. Proper supervision of the involvement of individual states in the ‘NATO + EU’ common security policy would be very effective in fighting hybrid threats. Thus, consolidating the activities of both organisations would create an effective global defence.

In addition, the use of ancillary tools (such as the Alliance’s Partnership Interoperability Initiative, which includes Ukraine, Sweden, Finland, Georgia, Jordan and Australia) even now makes it possible to strengthen cooperation within NATO. This is particularly important in view of the Russian Federation’s activities towards Ukraine and Georgia, which already allows threats to be monitored and appropriate support to be given to these countries.

From the perspective of the European Union’s functioning, the policy as defined in the Eastern Partnership[3]programme deserves particular attention. The initiative was launched in 2009 (the concept was proposed by Poland with the support of Sweden) and assumes strengthening ties with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine. The main objective of the Partnership is to strengthen multilateral cooperation at political and economic level.

Bearing in mind the fairly wide range of activities of NATO and the European Union a comprehensive and multi-faceted structure is being created. It enables response to security threats in a multi-phase manner. The improvement of the previously existing schemes, whether military, political, economic or social, allows for effective intervention and creates a geopolitical apparatus which today is of high necessity. In essence, such cooperation fully responds to the emerging challenges of hybrid threats.

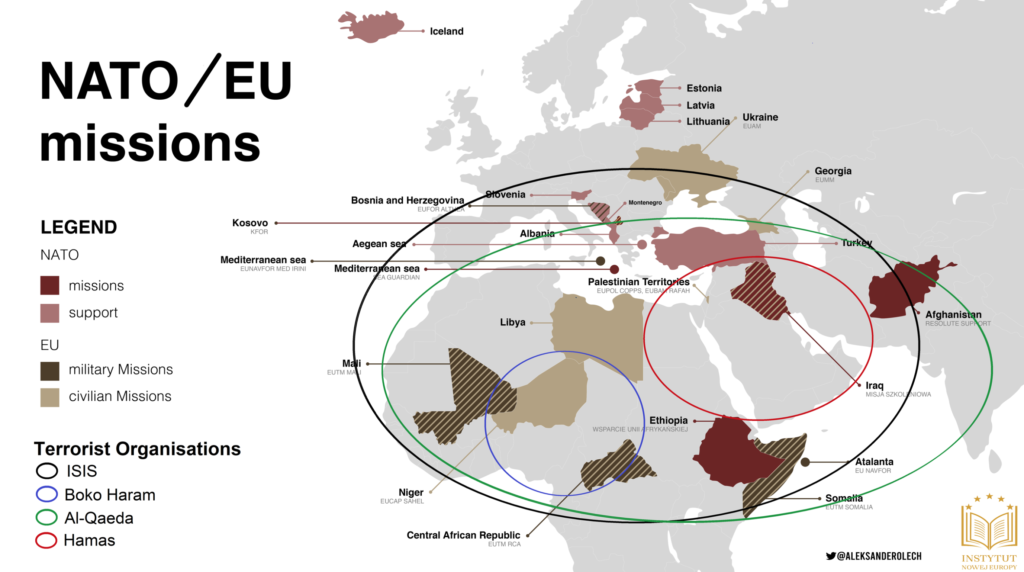

As it can be seen on the map, the missions of the European Union and NATO are intersecting in the most dangerous areas. It shows that both organisations have resources to conduct missions, but neither of them can cover every region that may be vulnerable to hybrid threats. For this reason, constant cooperation is necessary to minimise the risk of spreading threats. Moreover, most of the statutory goals of two institutions are the same, which should be a key to increase cooperation in the future. One of the main threats that must be eliminated is terrorism.

Terrorism is currently one of the biggest threats which must be highlighted from all hybrid threats. Terrorists are operating simultaneously in many countries using lethal methods against member states of the European Union and NATO. It is essential to emphasise the scope of terrorist activity as well as indicate in which areas international organisations should be concentrated on bilateral cooperation to minimise the risk of another attack. Moreover, all terrorist attacks impede global cooperation to carry out civilian and military missions in order to stabilise the situation in the host country.

It must be considered that the terrorist organisations, also perceived as a “hybrid actors”, are able to achieve real operational successes, as they attained major territorial expansions in Syria and Iraq.[1] In addition, the active presence of terrorists on the social networks for propaganda purposes also constitutes an important element of the hybrid activity.

In reference to terrorist organisations, the qualification of hybrid threats, therefore, becomes the trademark of fighting groups which are conducting irregular activities but possess certain significant capabilities considered as advanced, and which seemed previously the trademark of regular strategies of states. Furthermore, most of the non-state actors (terrorist organisations) do not have tools to conduct regular warfare but at the same time, they may be sponsored and participate in the indirect strategy of certain states.

Other actors in conflict

It’s worth taking a closer look at other countries which undertake actions that could be confidently considered as being hybrid in nature. The United States of America might be viewed as a mirror image of the Russian Federation if one considers its global involvement in almost all regional tensions and armed conflicts. The methods used by the US are most often military missions; however, they also use the media, cyberspace, and cooperation with civilians to convince the international community of the legitimacy of their actions. They often justify their increased activity in various regions of the world with the need to combat terrorism. It should be stressed that not all US actions could be logically explained (constant, international presence in many conflict regions) and not all of them have been actually carried out for peaceful reasons. Often the prospect of stabilisation has been illusory – as in the case of Afghanistan, for example. Therefore, countries which are not NATO members view the actions of the United States as a diversified form of gaining influence, i.e. hybrid actions on many fronts. There are many various factors influencing international conflicts. Misunderstandings often arise when a country expands its sphere of influence. It is therefore difficult to assess whether the real aggressor is Washington, or rather Moscow, Tehran and Beijing – all of which have their own grounds to react.

Therefore, it is equally important to view the issues of international security (safety environment) and hybrid risks involved from another perspective, too. This is crucial in order to understand the causes and reasons for other actors, such as Russia, Iran, China, India, Pakistan, Egypt, Algeria, or Palestine. This will make it possible to understand the rationale of world leaders and thus increase the knowledge of NATO and EU member states about their possible future actions. Such verification shall be a valuable experience and provide a strong basis for strengthening one’s own systems to combat hybrid threats. Understanding all parties involved in the conflict and obtaining information on their actions is crucial in developing one’s own security capabilities.

Conclusions

Since the annexation of the Crimea by Russia in 2014, many initiatives have been undertaken to strengthen the resistance of the EU and NATO to hybrid threats. These efforts must be recognised and their pace and intensity maintained. However, due to the ever-changing nature of hybrid threats, continued vigilance is required. Strategic approach towards combating hybrid threats, which would involve not only international but also national structures, including entire societies, as they are the main victims of terrorism, is essential. Only a multi-level security policy will enable the objectives to be achieved effectively in a dynamic environment of geopolitics. Both the EU and NATO have instruments of military and political cooperation for an effective response. However, it is crucial not only to eliminate emerging threats, but also undertake global initiatives to prevent them. In this respect, the main focus should be placed on the challenges in Central and Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East. However, for these to be carried out effectively, the commitment of each member state is essential. With no permanent and unwavering cooperation, the current efforts of international structures may turn out to be futile.

There are still a few obstacles that stand in the way of better cooperation of the EU and NATO. One of them is structural difficulties in delegating tasks to individual entities in particular countries – such process may often be extremely time consuming. Another one is rather slow exchange of information between the EU and NATO that leads to responding inefficiently and belatedly. There is also the lack of a unified strategy to fight hybrid threats in different regions. Those threats are perceived differently by member states of both organisations as well as cooperating countries. However, the European Union and NATO have demonstrated that there is a strong mutual will to strengthen security in the Euro-Atlantic area and to combat hybrid threats jointly. Institutionalisation and interdependence may not automatically lead to integration, but cooperation needs time to take a shape.

Main sources:

A. Hagelstam, Cooperating to counter hybrid threats, NATO Review, 23.11.2018, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2018/11/23/cooperating-to-counter-hybrid-threats/index.html, accessed: 29.08.2020.

Centre for Global Studies “Strategy XXI”, Ukraine – EU – NATO Cooperation for Countering Hybrid Threats in the Cyber Sphere, Kyiv 2019, p. 4–13, 27.

Council of the European Union, Complementary efforts to enhance resilience and counter hybrid threats- Council Conclusions, Brussels, 10 December 2019, 14972/19.

D. Fiott, R. Parkes, Protecting Europe – the EU’s response to hybrid threats, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Chaillot paper/151, April 2019, p. 11–29.

E. Bajarūnas,V. Keršanskas, Hybrid Threats: Analysis of Content, Challenges Posed and Measures to Overcome, „Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review” 2017-2018, nr 16, p. 123–131.

EU – NATO cooperation, EU Defence, June 2020, pp. 1–3, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu_nato_factshee_june-2020_3.pdf, accessed: 29.08.2020.

G. Hunter, The Mediterrane an Dialogue –A Transatlantic Approach, Arbeitspapiere zur Internationalen Politikund Außenpolitik, AIPA 2/2005, pp. 2-19.

G. Lasconjarias, J. A. Larsen, NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats, Rome 2015.

Hybrid Threats in EaP Countries: Building a Common Response, ed. K. Gogolashvili, Tbilisi, Chisinau, Kyiv, Erevan, Brussels 2019, pp. 36–39.

I. A. Cîrdei, Countering the Hybrid Threats, Military Art and Science, 2016, p. 113.

I. Lesser, C. Brandsma, L. Basagni, B. Lété, The Future of NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue – perspectives on security, strategy and partnership, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, June 2018, pp. 2-34.

I. Ploom, Z. Sliwa, Viljar Veebel, The NATO “Defender 2020” exercise in the Baltic States: Will measured escalation lead to credible deterrence or provoke an escalation?, Comparative Strategy 2020, VOL. 39, NO. 4, p. 368–384.

J. Gotkowska, Czym jest PESCO – miraże europejskiej polityki bezpieczeństwa, „Punkt Widzenia”, 2018, nr 69.

J. Richterová, NATO & Hybrid Threats, „Prague Student Summit“, 2016, nr XXI, pp. 6–19.

Ministry of National Defence, NATO missions and operations, https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/nato-missions-operations, accessed: 27.08.2020.

N. Helwig, New Tasks for EU-NATO Cooperation, „SWP Comment” 2018, nr 4, pp. 1-4.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO on the map, https://www.nato.int/nato-on-the-map/#lat=39.117723388627184&lon=6.377894848509222&zoom=1&layer-4&infoBox=510, accessed: 28.08.2020.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Operations and missions: past and present, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_52060.htm, accessed: 27.08.2020.

P. Pawlak, Countering hybrid threats: EU-NATO cooperation, Briefing, March 2017, European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament.

P. Szymański, Towards greater resilience: NATO and the EU on hybrid threats, „OSW Commentary”, 24.04.2020, nr 328.

S. Kwasi, J. Cilliers, Z. Donnenfeld, L. Welborn, I. Maïga, Prospects for the G5 Sahel countries to 2040, Institute for Security Studies, West Africa Report 25, November 2019, pp. 2-13.

T. Kubaczyk, Wojna hybrydowa – (czy) nowy typ konfliktu zbrojnego we współczesnym świecie, [w:] Konflikt hybrydowy na Ukrainie. Aspekty teoretyczne i praktyczne, red. B. Pacek, J. A. Grochocka, Piotrków Trybunalski 2017, p. 24.

The EU and NATO – The essential partners, ed. G. Lindstrom, T. Tardy, Paris 2019, pp. 5–20, 37–51, 63–72.

[1] E. Tenenbaum, La manœuvre hybride dans l’art opératif, Stratégique, No 111, Paris 2016, p. 56.

[2] Third progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorsed by NATO and EU Councils on 6 December 2016 and 5 December 2017. 31 may 2018.

[3] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO on the map, https://www.nato.int/nato-on-the-map/#lat=39.117723388627184&lon=6.377894848509222&zoom=1&layer-4&infoBox=510, accessed: 28.08.2020.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Operations and missions: past and present, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_52060.htm, accessed: 27.08.2020.

Ministry of National Defence, NATO missions and operations, https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/nato-missions-operations, accessed: 27.08.2020.

[4] Hybrid Threats in EaP Countries: Building a Common Response, ed. K. Gogolashvili, Tbilisi, Chisinau, Kyiv, Erevan, Brussels 2019, pp. 36–39

IF YOU VALUE THE INSTITUTE OF NEW EUROPE’S WORK, BECOME ONE OF ITS DONORS!

Funds received will allow us to finance further publications.

You can contribute by making donations to INE’s bank account:

95 2530 0008 2090 1053 7214 0001

with the following payment title: „darowizna na cele statutowe”

Comments are closed.