Article in short:

– With the emerging challenges to the security of the European countries and the unstable situation in Africa, Europe and the Maghreb should be perceived in terms of North-South.

– The Arab Spring and its subsequent consequences brought both: new challenges and opportunities for the Mediterranean Dialogue.

– NATO’s role in cooperation with the Maghreb countries will increase due to the ongoing war in Libya, the conflicts in Central Africa and the migration of militants from the Sahel into the continent’s deep.

NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue (MD) was launched in 1994 with the aim of advancing international security issues and the perspective of cooperation referred to as North-South. The regional security environment around the Mediterranean Sea is highly unstable and precarious, and the Alliance itself faces new strategic challenges. However, many of the core ideas are still valid, most notably the view that transatlantic security cannot be separated from security in the Mediterranean. Threats such as the conflicts in Syria, Libya, increased migration, terrorism, the phenomenon of international fighters, or tensions between Greece and Turkey should be mentioned. It is true that the objectives for security in the Mediterranean are probably closer than at any time in history if Europe and the Maghreb States are perceived in terms of North – South[1].

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, France, Italy, and Spain attempted to promote cooperation across the Mediterranean region through regional arrangements such as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in the Mediterranean and the Western Mediterranean Group. However, these initiatives did not develop successfully due to the civil war in Algeria and the introduction of international sanctions against Libya[2].

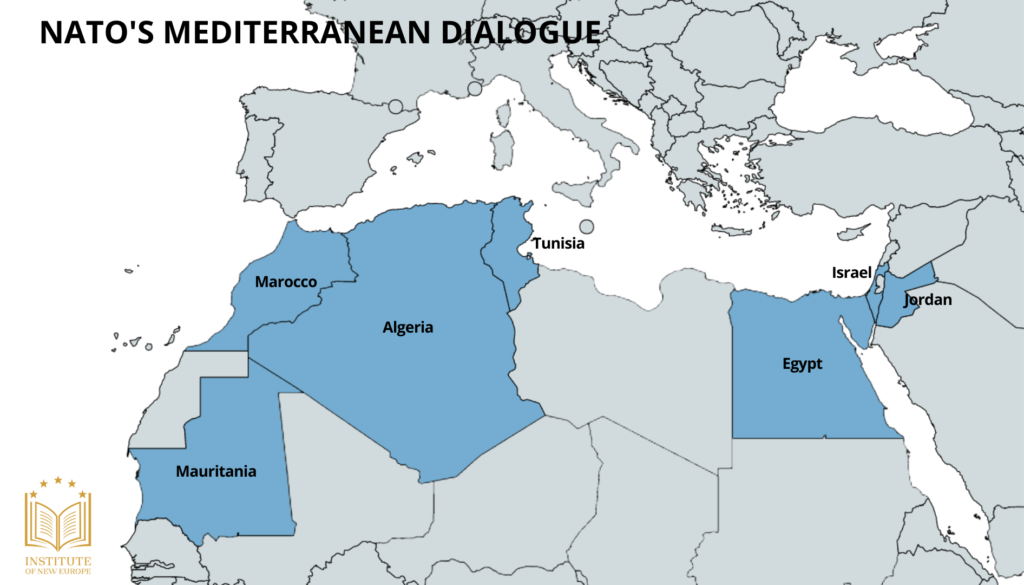

Simultaneously, a consensus was shaped among the member states of the Alliance as to the fact that stability and security in Europe are closely linked to stability and security in the Mediterranean region. Hence NATO’s decision in February 1995 to begin a direct dialogue with non-NATO countries in the Mediterranean region. After consultations with countries in the region, states such as Egypt, Israel, Morocco, Mauritania, and Tunisia accepted the invitation and became members of what later became known as the Mediterranean Dialogue. The number of participating countries increased from five to seven following the invitation to Jordan in November 1995 and to Algeria in February 2000. During the 1997 Alliance Summit in Madrid, the Mediterranean Cooperation Group (MDG) was established, bringing together representatives of NATO member states, together with their counterparts from the Mediterranean Dialogue countries, in order to conduct political debates in a multilateral format – member states plus all participants of the Mediterranean Dialogue. Currently, the MD consists of 7 countries: Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Morocco, Mauritania, Tunisia[3].

The “Arab Spring” and its subsequent consequences have brought both new challenges and opportunities to the Mediterranean Dialogue. The seven MD partners share an interest in engaging with NATO and consider the Alliance to be an influential strategic actor and practical contributor to their security needs. Perhaps this interest has increased in recent years as partnership activities have accelerated and been more closely aligned with partners’ interests due to threats such as international conflicts and terrorism. The Maghreb states that are NATO partners (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) are particularly eager to work with the G-5 Sahel group (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger)[4] and to deepen the commitment to the security challenge[5]. Including jointly control borders, fight terrorism, develop cyber security, protect the population.

Currently, the objective of the Maghreb countries is to have permanent access to NATO courses and training, which will be an important element of strengthening their security policy in the region. The exception is Libya, where war is raging and MD countries avoid getting involved in it. NATO’s role is limited to the Sea Guardian Mediterranean Security mission, an operation carried out in order to: maintain security, counter-terrorism, build defense capabilities in the region, protect freedom of navigation and critical infrastructure, and help maintain cooperative security with other actors in the region[6].

It seems, therefore, that the role of NATO will be increasing in the region, especially in cooperation with the Maghreb countries. This is extremely important not only due to the ongoing war in Libya, conflicts in Central Africa, or the migration of fighters. The main goal is to strengthen North-South cooperation in which, within the engagement in the activities of the North Atlantic Treaty, it is possible to create a stable security environment in cooperation between Africa and Europe.

[1] I. Lesser, C. Brandsma, L. Basagni, B. Lété, The Future of NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue – perspectives on security, strategy and partnership, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, June 2018, p. 2-34.

[2] G. Hunter, The Mediterrane an Dialogue –A Transatlantic Approach, Arbeitspapiere zur Internationalen Politikund Außenpolitik, AIPA 2/2005, p. 2-19.

[3] I. Lesser, C. Brandsma, L. Basagni, B. Lété, The Future of NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue – perspectives on security, strategy and partnership, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, June 2018, p. 2-34.

[4] S. Kwasi, J. Cilliers, Z. Donnenfeld, L. Welborn, I. Maïga, Prospects for the G5 Sahel countries to 2040, Institute for Security Studies, West Africa Report 25, November 2019, p. 2-13.

[5] NATO Allied Command Transformation, Understanding the G5: governance, development and security in the Sahel, Volume 3, Number 2, Spring 2019, p. 2-11.

[6] I. Lesser, C. Brandsma, L. Basagni, B. Lété, The Future of NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue – perspectives on security, strategy and partnership, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, June 2018, p. 33-34.

IF YOU VALUE THE INSTITUTE OF NEW EUROPE’S WORK, BECOME ONE OF ITS DONORS!

Funds received will allow us to finance further publications.

You can contribute by making donations to INE’s bank account:

95 2530 0008 2090 1053 7214 0001

with the following payment title: „darowizna na cele statutowe”

Comments are closed.