With the return of Great Power Competition, instability is rising in certain parts of the world, and economic growth becomes strained by political factors challenging to assess. However, institutions, international safety and connectivity are still the backbone of fast growth and capital value development.

In this context, Poland increasingly appears as one of the last untapped reserves of value creation. Moreover, its integration in the EU, NATO, its very close ties to the US, and its role as a regional leader are opening very promising perspectives to the Polish economy.

Internal security

Corruption is very limited in Poland. The country is ranked 44th in the 2020 International Transparency Corruption ranking, which is not far from France (23rd), the US (25th), Spain (32nd), South Korea (33rd) or Israel (35th), and better than the Czech Republic (49th), Italy (52nd), Hungary (69th) or China (78th). Comparing Poland to countries such as Russia (129th) is of little interest.

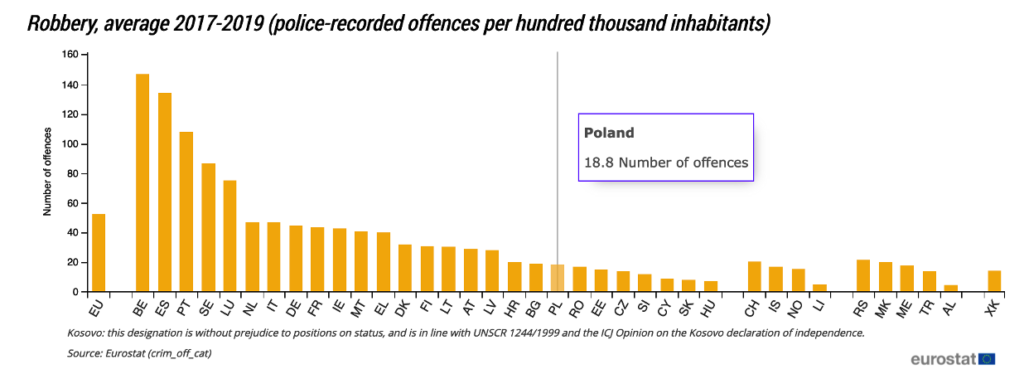

Overall, Poland is among the safest countries in Europe, with very low robbery (chart below) and criminal offence rates. According to Eurostat, Poland’s criminal offence rate is around 3%, while the European mean is 11%.

A skilled society

In the OECD study Skills Matter, Poland figures among the best-ranked nations, with 60% of 25-34 years-olds holding tertiary education degrees, just above the US and significantly higher than the OECD average, which stands at 52%.

50% of recent tertiary graduates are overqualified for their job, which is the highest rate in the OECD, after the Slovak Republic, Croatia, Italy, the Czech Republic and Portugal. However, Poland displays also one of the most significant differentials in overqualification between recent and older graduates. Only 30% of older graduates (+35 years old) are overqualified, which the increasing quality of education can explain, but also of jobs. In other words, there is still substantial potential for jobs improvement, and salaries rise.

The EF English Proficiency Index ranks Poland 16th out of 100 nations, which is ahead of Switzerland (18th), France (28th), Italy (30th), South Korea (32th), Spain (34th) or even Japan (55th).

It is worth noting that this has been achieved despite a level of education spending lower than the OECD average: about 5% of GDP.

However, Poland’s successes in the field of education should not come as a surprise. Poland has nurtured quantities of world-class scientists throughout history. Among the most famous: Copernicus, Hevelius, Sklodowska-Curie, Banach (the founder of functional analysis), Tarkowski (in vitro fertilization), Cybulski (adrenaline), Hurwicz (game theory), Charpak (particle detectors), Drzewiecki (1st electric submarine), Lukasiewicz (1st oil refinery & oil well), Bryla (1st welded road bridge), Ulam (Manhattan Project, Teller-Ulam design), Kosciuszko (West Point fortifications), Kosacki (mine detector), Bekker (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Funk (vitamins), Konorski (neural plasticity), Hoffmann (chemical reactions), Olszewski (liquefied oxygen), Malinowski (among the founders of anthropology), Proszynski (1st film camera, before the Lumiere brothers), Sendzimir (industrial-scale galvanizing), Steinhaus (game theory & probability theory), Wolfke (holography & television), Zglenicki (oil extraction from sea bottom), Wolszczan (extrasolar & pulsar planets), …

Value creation through geostrategic leverage

The importance of NATO and of Poland’s very close relationship with the US for its development cannot be stressed enough. It is what Andrew Michta, one of the most acute geopolitical experts of the region, does frequently: “The stunning transformation of post-communist Europe after 1990 was possible not only because of the powerful appeal of democracy and markets, but above all because Russia was literally expelled from the region. […] National security and state sovereignty were the sine qua non of the successful transformation of post-communist Central Europe”.

The strengthening of transatlantic ties is then of crucial importance to Poland, especially since the decline of the US is a myth, as I argue in my paper Global Systemic Cycles and the Current Transition: An Interdisciplinary Reflection About Global Growth, Economic Cycles, and Great Power Competition.

Poland spends 2,4% of its GDP – more thus the 2% NATO requirement – on its defense, multiplying American equipment purchases, like F35 fighter jets and M1A2 Abrams thanks lately, making the Polish army interoperable with American armed forces.

The US is set to increase its military presence in Poland with 1000 additional troops in the framework of an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.

The US has pledged a $1b investment in the Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund (3SIIF), which objective is to “invest in transport, energy and digital infrastructure on the north-south axis in the Three Seas countries and to offset the differences in the development of individual regions of the European Union”. This US-supported fund is intended to receive public as well as private investments from around the globe.

The special US support from which benefited certain strategically situated countries has been highly beneficial to their development. Remarkable instances of this are Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Israel. Poland, along with other Central and Eastern European nations, is the latest such key ally.

A diversified and industrialized economic portfolio

A winner in the international trade competition

The Covid crisis has brought a new wave of investments into Central Europe. As underlines Patrick Artus, Natxis’ Chief Economist: “When we look at recent developments, we see a much better resilience of production, industry, investment and employment in Central European countries relative to euro-zone countries, which shows the importance of the competitive advantage of Central European countries”. Capital and jobs are moving from Western Europe to Eastern Europe: “France’s external deficit is with Europe and not with emerging countries. […] France has a disadvantage in terms of both cost competitiveness and non-cost competitiveness (product sophistication, skills)”. There is a rebalancing of the distribution of wealth in Europe following the delay in economic development that Central Europe has suffered during the 20th century.

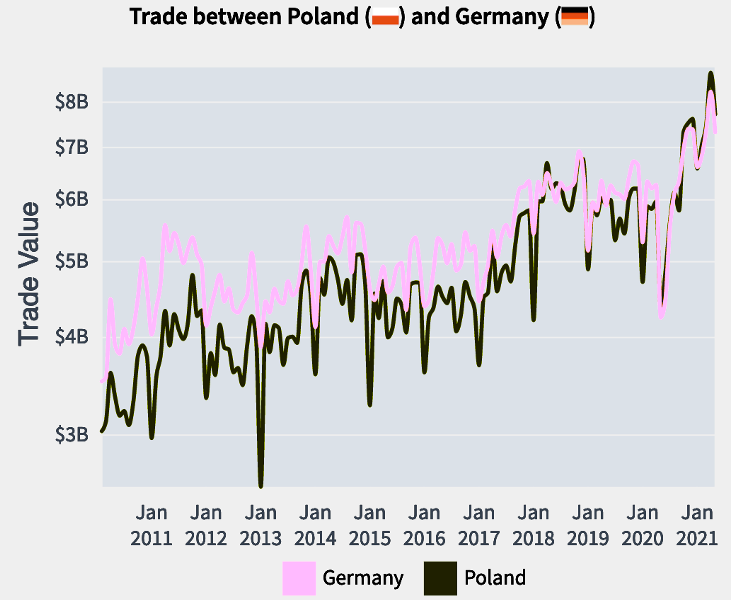

In 2020, Poland has overtaken Italy and France to become Germany’s 4th biggest import partner (~$68b), after China, the Netherlands and the US. In April 2021, Germany imported $7,72b worth of goods from Poland (chart on the right), and Polish-German trade has been growing at a fast pace in 2021.

This is proof that Poland’s economy is rising in the international value chain, its products becoming more valuable to German companies while still cheaper than those of Western European nations.

Moreover, Poland is a perfect candidate for the services delocalization wave brought by the Covid crisis and the remote work trend.

Overall, Central Europe’s economic dynamic is profoundly different from Western Europe, where automation paradoxically tends to lower the skills sought by employers. The Western European wage level is no longer adequate for these jobs.

An effervescent job market

Unemployment in Poland is exceptionally low (3,5%), which results in steep wages growth: 6,6% in 2019 (4,8% in real wages terms), and 5,1% in 2020 (1,2% in real wages terms).

The overabundance of jobs is answered mainly by the inflow of Ukrainian workers (532k at the end of 2020, 75% of all foreign workers). In 2020, Poland also issued the largest number of first residence permits granted in the EU to non-EU citizens: 598k (26% of the total).

Climbing the value chain: the Morawiecki plan

A comprehensive development strategy, the Morawiecki plan, has entered into force in 2016 to prevent Poland from falling into five development traps: stagnating salaries, capital flight, average products, demographic imbalances, weak institutions.

One of the most striking effects of this plan has been the creation of the Polish Development Fund, which operates in a comparable way to the French Caisse des Depots. It has so far invested ~$5.5b in Polish companies, of which $200m in start-ups. As we see below, this has been a profound game-changer.

An underleveraged economy

Polish sovereign debt amounted to only 57,5% of GDP at the beginning of 2021, and household debt to 35,4%.

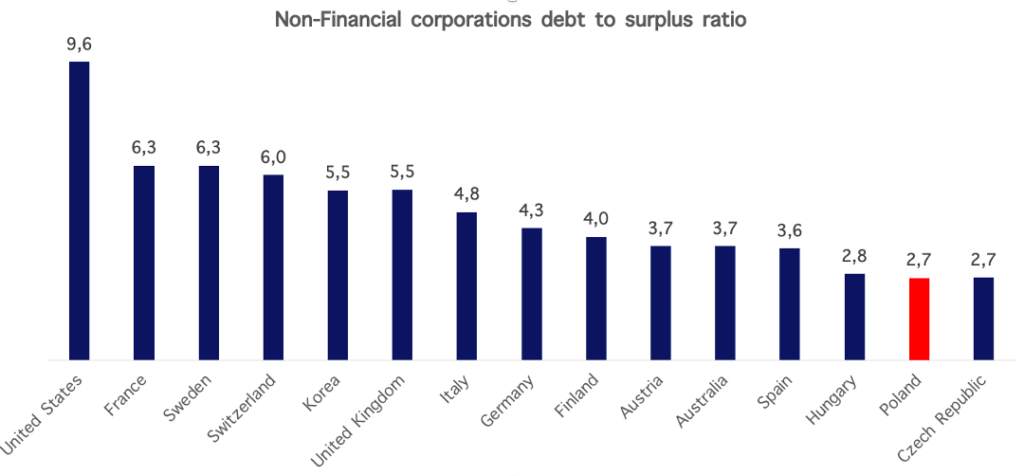

Polish companies are severely underleveraged too. This can be partly explained by a cultural fear of debt related to the country’s previous heavy reliance on foreign debt and the relatively small size of polish family businesses, and their frequent lack of financial knowledge.

Financial independence

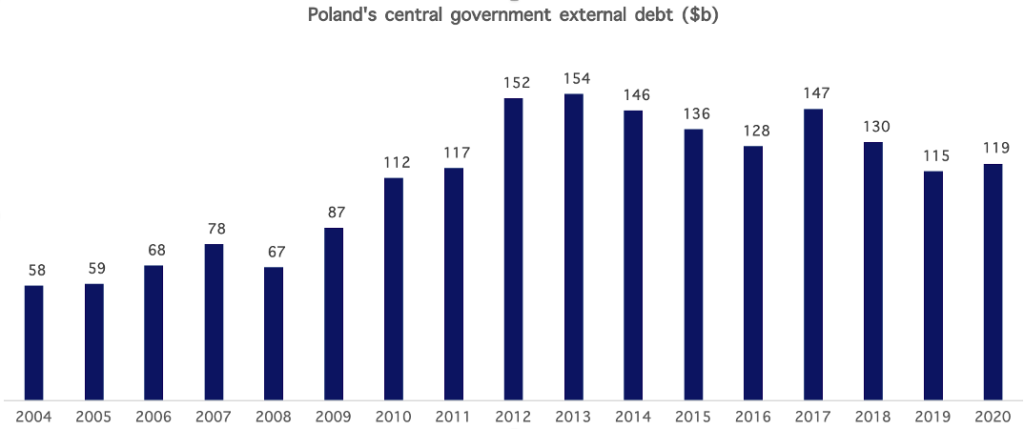

Poland’s reliance on external debt is rapidly ending since it now accounts for only 32% of its total central government debt, compared to 56% in 2013.

Lightspeed infrastructural development

The Polish railway will receive $75b in funding during the 2021-2030 period.

A new international airport, the Solidarity Transport Hub, will be launched in 2027 at an estimated $9b.

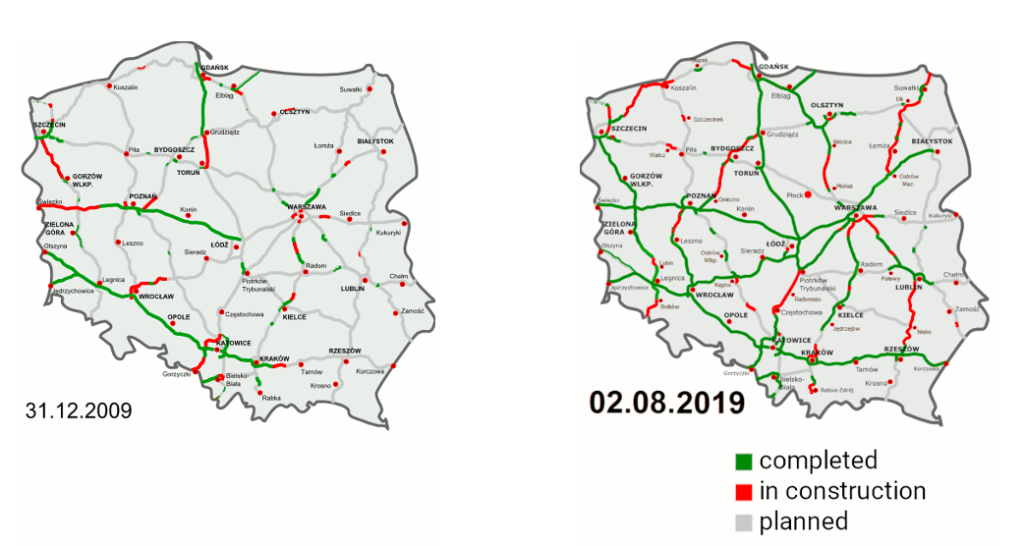

$36,6b is being invested from 2014 to 2023 in road infrastructure. Here is a map that shows the speed of Polish highways construction:

A natural regional leader

Poland’s financial infrastructure is the most solid in the region, making it the main gateway between international investors and Central European economies. According to the Swedish economist Anders Aslund, “the post-communist countries have failed to develop sound stock markets. The only real success is Poland. […] For many countries, this means that an IPO should take place either in Warsaw or at a Western stock market.”

Poland has so far contributed the most significant amounts to the Three Seas Fund ($850m) and leads the block. The Three Seas Fund’s purpose is to invest in transport, energy and digital infrastructure on the north-south axis in the Three Seas countries. As analyses Pierre-Emmanuel Thomann, the motivation behind this is that “the current infrastructure is oriented in an east-west direction. The inherited infrastructure, built during Cold War times, are perceived as factors of geopolitical dependence on Russia, the main energy provider in the area, and reinforcement of Germany’s economic dominance since the EU enlargement to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe”. The total number of projects under the Three Seas Initiative is currently 90, grossing an estimated investment value of ~$210b. In other words, the Initiative has the potential to redefine European trade.

In 2019, exchanges of the Three Seas region have agreed to create the new CEEplus index. It includes the largest and most liquid stocks listed on the exchanges of the Visegrad Group countries (PL, HU, SK, CZ), Croatia, Romania and Slovenia. The index is the underlying of a passive fund managed by the Polish TFI PZU and floated on the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

It should be noted that this role is made possible by the close alliance with the US and its support for the project, which, as the geopolitical analyst and director of the AIES, Velina Tchakarova, points out, “is not only setting its foot in the neighborhood but also hopes to lure the region to its side”.

Comments are closed.