Main points

• Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012 initiated a new, more confrontational model of PRC’s foreign policy, symbolised by the so-called “wolf-warrior diplomacy”. The uncompromising pursuit of the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” has replaced the prevailing until recently concepts of “low profile” and “peaceful development”.

• The main goal of the PRC’s policy is to maintain the current variant of globalisation based on the relatively free movement of capital, goods, services, and knowledge, which enabled China to expand globally. However, the growing intensity of competition with the US generates more and more obstacles to further development.

• The most serious external barrier to China’s super-power ambitions is a revisionist policy driven by nationalist sentiment, both in the near neighbourhood and at the global level. This generates growing tensions in both close and distant neighbourhood (Japan, India, Australia, Vietnam, Great Britain, Canada, the Czech Republic).

• China is pursuing ambitious policies in the developing countries of Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Infrastructure investments, connectivity, credit lines, and imports of raw materials are the main tools for building influence and gaining political support. Most of these types of projects are implemented under the Belt and Road Initiative, which is the flagship project of the Xi Jinping administration.

• In the strategic dimension, Beijing seeks to use the weakening position of the United States to remodel the regional order in Asia, as well as in international institutions. This agenda includes an attempt to weaken the transatlantic relationship that underpins the current Western-dominated order. For this reason, China supports ‘multipolar’ system and the ‘strategic autonomy’ of Europe, as well as the order based on state sovereignty and the principle of non-interference.

• While the global struggle with the US remains a defining challenge for China, Beijing aims to deepen ties with the countries resisting the American supremacy. Among them Russian Federation remains a key partner that provides Chine with political support, raw materials, and advanced military equipment.

China’s foreign policy concepts

Since Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012, the importance of unilateral tendencies in People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) foreign policy has increased, and the new authorities have significantly intensified their external activity aimed at securing the so-called “vital interests” ( Héxīn lìyì核心利益) [1]. There has been a clear departure from the Deng Xiaoping’s ‘24-Character Strategy’ and ‘peaceful development’ promoted by Hu Jintao[2] to the ‘great power diplomacy’ (大国外交Dàguó wàijiāo )[3] and the policy of ‘striving for achievement’. Particular elements of the previous concepts are still present in Beijing’s activities, but they play an incomparably lesser role than in the previous decade[4].

Xi’s administration’s central idea became the pursuit of the “Chinese Dream” and the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (Zhōnghuá mínzú de wěidà fùxīng中华民族的伟大复兴)[5], which officially aims at improving society’s standard of living. This is reflected in the “goals for two centuries” (两个一百年)[6], the first of which is achieving a “moderate welfare society” by 2021 and the second – creating a “modern socialist state” by 2049.

The ” Rejuvenation” should also be considered in the context of China’s pursuit of territorial and political restitution of its central position in Asia. In practice, the implementation of the ‘Chinese Dream’ would mean not only improving society’s level of prosperity but also extending full control over all of the territories to which China reserves its ‘sovereign rights‘ (Hongkong, Taiwan, South China Sea, Senkaku Islands[7]. Beijing’s ultimate ambition is shaping a new order in Asia that would put China in the main spot and would make values, communication links, as well as investment and commodity flows to be centred around it. The economic dominance would be supported by controlling the most important maritime connections (SLOCs) in the Western Pacific and Eastern Indian Ocean. Achieving these goals would require pushing American troops out of the first chain of islands, in addition to a disintegration of the San Francisco alliance system.

The new foreign policy of China can be characterised by both an intensified activity and an increased level of assertiveness, which has become particularly noticeable during the Covid-19 pandemic. The confrontational way of conducting diplomacy was dubbed ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’ (战狼外交) and so far has led to some serious crises in relations with Australia, India, Canada, Sweden, and Great Britain. As a result, China has missed the opportunity created by the weakening of the US global leadership during the pandemic. Confrontational actions undertaken by Chinese diplomats have made the narrative of the Chinese threat more credible, therefore resulting in an increased possibility of forming an anti-China coalition in the Indo-Pacific area. At the same time, political support for the idea of economic “decoupling” has increased, which can be seen particularly in the case of the US, Japan, and Taiwan.

The flagship project of the Xi administration, designed to promote China’s vision of globalisation, is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – also known as the New Silk Road – which was announced in 2013[8]. In the long term, the BRI is expected to create a new system of economic, infrastructural, and political links that would guarantee China opportunities for further development, especially when it comes to its north-western provinces, and consolidate the influence in the immediate and further neighbourhood. The initiative’s character is not clear-cut – this project can rather be described as a comprehensive framework within which all the constructive actions undertaken by the Chinese diplomacy and state-owned companies are being integrated. Despite this ambiguity, the BRI creates a narrative for the PRC’s international policy and serves as a proposal for the Chinese vision of globalisation.[9].

As power is increasingly concentrated in the hands of Xi Jinping and his political allies, the Secretary General’s personal contribution to China’s diplomatic conduct is increasingly emphasized [10]. It is a reflection of practices that used to be in place during the ‘Mao era’, when Mao Zedong’s ideas and considerations, at the very least in the public discourse, served as a compass for the Beijing’s diplomacy.

Xi Jinping’s international visits and main directions of PRC’s foreign activity

The overview of Xi Jinping’s international trips largely reflects the priority directions of China’s diplomacy, which in turn corresponds to the current strategic and economic interests. His bilateral visits to countries defined as rather middle or small powers are usually accompanied by the signing of infrastructural contracts and economic agreements, often within the BRI framework. As if often happens, Xi’s visits to smaller countries are associated with the competition for influence with other foreign powers, and the arrival of the Chinese head of state is aimed at reorienting the politics of a given country (i.e., Sri Lanka, or the Maldives). When it comes to relations with other ‘great powers’ (the US, Russia, India, Brazil, Germany, or France), the agenda of meetings is so comprehensive that announcing spectacular infrastructure contracts is simply not necessary.

Nevertheless, it has to be emphasised that the mere number of Xi’s visits in a given country should not be regarded as a fully credible indicator of its importance for China. For instance, though Pakistan remains China’s key partner in the Indian Ocean basin, and that is where the largest BRI’s project – the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – is located, Xi Jinping visited this country only once. Nigeria’s case is very similar in this regard – Beijing’s investment and infrastructural commitment there since 2005 is valued at USD 40,98 billion[11], but China’s leader has not decided to pay a visit to Abuja yet. These examples clearly show that the mere number of Xi’s visits in a given country ought to be regarded only as a supplement to a broader analysis based on research that takes into account more complex factors of economic, political, and historical nature.

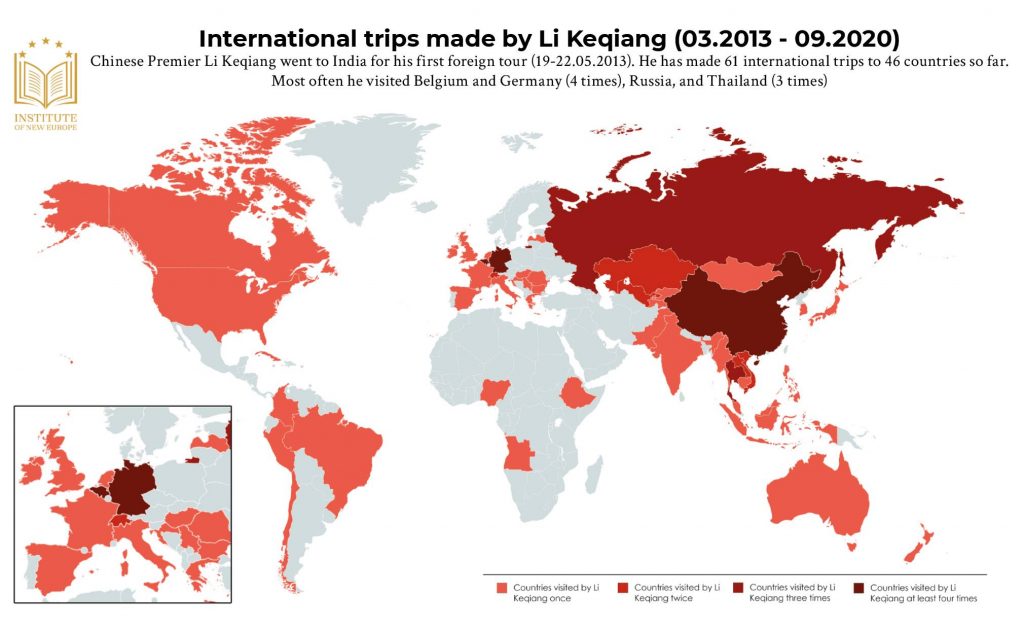

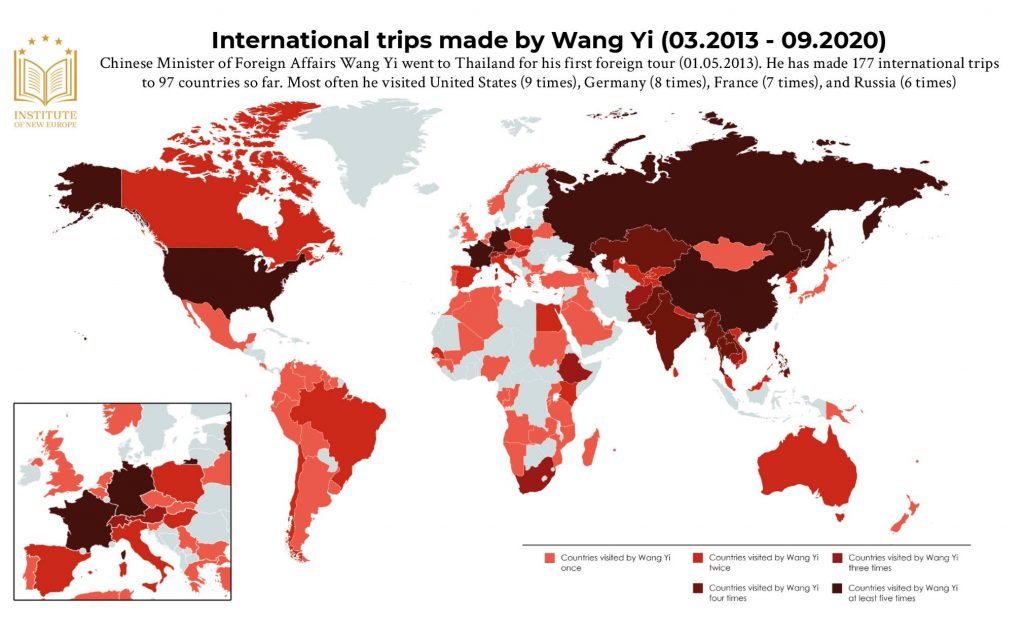

More frequent visits to some states may also result from the fact of their hosting of some of the regional and international forums, such as BRICS, APEC, FOCAC, or G20. President’s activity is also often complemented, or replaced, by the presence of China’s prime minister Li Keqiang or foreign minister Wang Yi, both of whom remain active through their participation in other formats such as China-ASEAN, 17+1, China-CELAC Forum, and others. Only taking into consideration all of the aspects of the external activity mentioned above allows for creating a relatively complete picture of PRC’s foreign policy priorities.

Russian Federation

It is not a coincidence that Russia is the most visited country by the Chinese leader. In the previous decade, the cooperation between Beijing and Moscow significantly intensified, owing to both countries’ deteriorating relations with the US and other Western states, as well as the diplomatic and economic isolation of Russia[12]. The global economic crisis of 2008-2011 contributed to Moscow’s plan of ‘turning to Asia’[13], which was mainly driven by economic incentives[14]. Amongst them, the ones of greatest importance seem to have been the export diversification[15], as well as accelerating the development of the Eastern Siberia through encouraging investments from China, Japan, and South Korea[16]. Following Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014, Moscow’s relations with Beijing gained additional momentum in the result of sanctions introduced by the Western countries. The principal factor in the Russia-China collaboration is both countries’ aim to undermine the US’s superiority and creating

a polycentric international system, which would guarantee a stronger influence and position for them. The coordination of political actions and similar strategic perception is illustrated, among other things, by both countries’ similar voting patterns in the UN Security Council[17]. Russia remains – along with Saudi Arabia – China’s main source of oil imports, and the inauguration of the Power of Siberia pipeline will allow for an increase in natural gas purchases[18]. Since 2010, China has been Russia’s most important economic partner – in 2018, the value of commodity exchange between them exceeded USD 106 billion[19]. It is highly important for Beijing to secure the supply of modern armament (Su-35 air-fighters, S-400 missile system, or the AL-31F jet engines), which allows to partially supplement the technological deficits of the Chinese arms industry. Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin are known for their cooperation in BRICS, G20, and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which imposes a higher frequency of contacts between both leaders. In the face of worsened relations with Western countries, the presence of Xi Jinping at events of particular importance for Russia – such as the Sochi Olympics in 2014 and the Victory Day Parade in 2015 – serves also as a symbolic expression of support. The dynamics of bilateral relations to date suggest that they will deepen in the medium-term (2030), just as will the scale of Russia’s economic dependence on China.

The US

The US is the second most visited country by the Chinese leader. However, three out of four Xi’s trips to the USA took place during the Obama presidency (2013, 2015, 2016). Even though it was the Obama administration that initiated the turn towards Asia[20], it was not explicitly anti-Chinese in its tone. The only visit paid by Xi to the US during the presidency of Donald Trump occurred in April 2017, soon after the latter was sworn into office. The meeting was designed for working out a relationship between two leaders after an aggressive US presidential campaign, during which Trump accused China of ‘the greatest theft in the world’s history”[21]. As it can be observed lately that meeting did not prevent the escalation of tensions between the two countries. Quite to the contrary, the US-China relations significantly worsened due to a number of factors, including the trade war, military competition in the Indo-Pacific region, sanctions introduced against Huawei, and the dispute over the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of that, another trip of the Chinese leader to the US seems to be rather unlikely. Potentially, Xi’s next visit to the USA could be initiated by a breakthrough in trade negotiations, or it could serve as an attempt for a new opening in bilateral relations if Joe Biden wins the election in November 2020.

East Asia (Japan, South Korean, North Korea)

Relations with Japan and South Korea are of key importance for the security and economic development of the PRC. Despite intense economic cooperation, the relations between the above-mentioned countries are complex due to their divergent security interests. In the strategic domain, Tokyo and Seoul are among the vital US allies in Asia, which provide the US military with the ability to maintain the forward defense line in the Pacific. About 85,000 military personnel, several dozen bases together with equipment and infrastructure facilities, and agreements with South Korea and Japan are considered by Beijing as one of the main barriers to securing the “core interests” of the PRC. Japan’s growing activity in the Quad format (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) and the ambitious modernisation program of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) are seen as a threat to China’s regional ambitions.

China remains a de facto “ally” of North Korea, which, through economic and technological support, made it possible for the totalitarian regime to survive after the end of the Korean War. North Korea is considered to be a strategic buffer between China and the US military, and Beijing sees upholding the anti-American regime as a strategic imperative. The North Korean nuclear program is perceived by East Asian states as one of the main sources of instability in the region. The main obstacle to the policy of unification is the concern of the Chinese leadership regarding the possibility of a Korean state which would remain allied with the USA and the coalition Washington is forming in the Indo-Pacific region. At the same time, Beijing is interested in both limiting North Korea’s nuclear arsenal and aggressive behaviours, due to the risk of an undesirable escalation of tensions in the region, and deepening cooperation with South Korea.

In the economic dimension, there are strong interdependencies between China, Japan, and South Korea resulting from their participation in regional production chains, mainly in the electronics sector. In 2018, trade with South Korea amounted to USD 313 billion, and with Japan to USD 323 billion[22]. In total, this is a result higher than that of trade with the USA (USD 558 billion)[23] and the European Union (EUR 560 billion in 2019). As concerns about the stability of relations with China grew, the debate over transferring parts of production chains from China to Southeast Asia has gained momentum. Beijing will strive to maintain intense trade and investment contacts with South Korea and Japan and to counteract these dangerous trends.

The 2010-2020 decade saw a marked increase in tensions between China, the United States and its allies. China’s actions to gain effective control over the first chain of islands and intimidate the states that stand in the way have exacerbated the security dilemma in East Asia. In the coming years, China will take steps to use the relative erosion of the US position to strengthen its influence over the rest of Asia. The rising military potential of China, the “North Korean card”, and economic considerations will serve as primary tools.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asian countries, such as Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, enjoy quite a significant position on Jinping’s list of diplomatic priorities. This region is of key importance for both the economic and military policy of China. In 2019, trade with countries constituting ASEAN reached USD 642.5 billion[24] (only indicators for trade exchange with the EU were higher), and in the first half of 2020, it was the ASEAN members that achieved the status of the PRC’s most important economic partner, ahead of the European Union and the United States.

Furthermore, in the last decade China became the main investor in the region: in 2017 Chinese companies invested USD 14 billion in the ASEAN member states, and USD 10 billion in the following year25]. These estimates, however, do not take into account investments from Hong Kong (USD 6 billion and USD 10 billion respectively). Investments and infrastructure remain one of the main areas of economic competition with the USA, Japan, and South Korea. Chinese companies are responsible for such infrastructure projects as the ECRL railroad (Malaysia, USD 13 billion), a hydroelectric power plant on the Kayan River (Indonesia, USD 17.8 billion), Vietnam-Kunming railroad (Laos, USD 6.5 billion), Muse-Mandalay railroad (Myanmar, USD 9 billion), or Kyakpyu port (Myanmar, USD 1.3 billion). On top of that, an announcement of another investment (an airport close to the Philippine’s capital, Manila) was made this year[26].

Geographical conditions make the countries of Southeast Asia play an important role in maritime trade in the Indo-Pacific area, which is best illustrated by the significance of the Straits: Malacca, Lombok, and Sunda. Moreover, it is also the states of the region that continue to be the most important parties to the territorial dispute over the South China Sea, the resolution of which is among the most important objectives of Chinese diplomacy. For the aforementioned reasons, the vision of the Maritime Silk Road was announced by Xi Jinping during his visit to Indonesia in 2013[27]. The BRI is supposed to be a counterbalance[28] for the concept of ‘A Free and Open Indo-Pacific’[29], promoted by the US, Japan, and Australia, which is considered by Beijing as a beginning of the anti-Chinese coalition[30]. With enhancing cooperation within the Quad format, maintaining neutrality by the countries of Southeast Asia moves up to the forefront of China’s foreign policy agenda. Building and preserving a strong position in China’s immediate neighbourhood holds significant importance for both economic and strategic reasons.

South Asia

The importance of South Asia for the PRC’s diplomacy is demonstrated by the fact that Xi Jinping has visited all countries of this region, except for an unstable Afghanistan. India and Pakistan are at the forefront of China’s diplomatic activity in the South Asua, due to their economic and strategic significance. While the former country is a regional competitor in the struggle for influence in the Indian Ocean basin, it is also an important economic partner for China. India’s status may eventually shift from a regional power to truly great power. To this day, New Delhi has pursued a policy of keeping a relatively equal distance from all of the major powers, an illustration of which is the fact of preserving cooperation with Russia, USA, as well as China[31]. Escalated tensions after the clash that took place in Eastern Ladakh, may cause the reorientation of India’s strategy and enhancement in the military cooperation with the US and other states constituting the Quad format. Pakistan has been one of China’s closest partners, and the relationship between both states has been dubbed as ‘all-weather partnership’(Zhōng bā quántiānhòu huǒbàn guānxì中巴全天候伙伴关系)[32]. The importance of Pakistan stems from the role it can play in counterbalancing India’s rise and the possibility of gaining direct land access to the Indian Ocean through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Gwadar port. Beijing’s growing maritime ambitions ought to be reflected in the future in an increased activity in the South Asian countries, through which China will be promoting economic and investment cooperation within the Maritime Silk Road.

China already remains strongly committed to the development of infrastructure in the South Asian countries, which is meant to provide an impetus to expand its influence at the expense of India. For instance, during a visit to Bangladesh in 2016, the launch of an economic package worth USD 24 billion (only USD 1 billion real investments to date) was announced. In the cases of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, Xi Jinping’s visits were supposed to provide an impulse for an increased China’s presence in the Indian Ocean. China’s value for infrastructural investment in Sri Lanka in the period 2006-2009 was estimated at USD 12 billion, and USD 6.8 billion were invested between 2013 and 2019[33]. In the Maldives, Chinese companies are responsible for infrastructure projects valued at USD 1.3 billion, and – according to some reports – up to 80% of the foreign debt of this country (25% of GDP) is attributed to China. Beijing’s growing involvement in this region will cause additional tensions with India, which perceive such activity simply as violating its traditional sphere of influence[34].

Central Asia

Central Asia is one of the most frequently visited regions by Xi Jinping, largely because of the increasing energy cooperation, the location of the region’s countries on the New Silk Road, and the participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Xi’s administration continues its efforts to diversify energy sources, and natural gas imports from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan constitute an important part in this plan. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are China’s main trading partners in the region (USD 8.52 billion import/USD 11.32 billion export; USD 8.2 billion import/USD 0.31 billion export; USD 2.32 billion import/USD 3.94 export respectively)[35]. In 2018, Central Asian countries exported 46.8 bcm of natural gas through the Central Asia-China pipeline, which was three times more than to Russia (16.1 bcm)[36].

An important part of the PRC’s activity in Central Asia are both direct investments and infrastructural projects. In 2018, Chinese FDI was valued at USD 14 billion[37], and the total amount of investments and contracts for the period 2005-2020 was estimated at USD 55 billion[38]. Over the past few years, credit lending has been increasing. The main recipients of loans from Chinese national banks are Kyrgyzstan (USD 17.14 billion; 45.3% of foreign debt), Kazakhstan (USD 12.5 billion, 8.9 % of foreign debt), and Tajikistan (USD 11.62 billion, 51.1 % of foreign debt)[39].

Furthermore, Central Asian countries collaborate with China within the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation format, whose main goals are preventing separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism[40]. Upholding stability in the border region is important for Beijing simply because it supports the efforts to eliminate autonomous movements in Xinjiang. Cooperation in this format facilitates more frequent contacts between regional leaders and President Xi Jinping. Since 2013, as many as five out of eight summits have been held in the Central Asian countries belonging to this organization. It was also in Kazakhstan’s Astana in 2013 that the Chinese leader announced the project of the New Silk Road[41], which shows that the countries of the region are regarded as an important element of China’s strategy in Asia. Russia’s economic problems, the lack of a strong US presence, and China’s economic potential mean that Beijing will play a major role in the region’s development policy in the coming years.

Latin America

There are three reasons for relatively frequent Xi Jinping’s visits to Latin America. Firstly, Latin America plays an important role in the PRC’s energy and resource policy and it is in Beijing’s interest to maintain good relations with its key economic partners in the region. Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and Peru are the main source for the Chinese import of soybean, metals, minerals, and hydrocarbons, and these commodities constitute 75% of Chinese total imports[42]. Secondly, as many as three Xi’s trips to Latin America (two to Brazil and one to Argentina) were linked to international formats’ summits (BRICS and G20) and thus were not of bilateral character. Lastly, Latin American countries can be valuable political partners for China. Similarly to Africa, Latin America used to be considered as part of the so-called ‘third world’, and even though the postcolonial past is rather a nonimportant factor in the relations between China and Latin American countries, it has to be emphasised that their lack of permanent and durable alliances with the US paves the way for growing political influence by China. This applies particularly to countries with rather small potential and lower levels of development, for which participation in the BRI provides an opportunity to stimulate economic cooperation.

Economic difficulties caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, together with the Latin American countries’ dependence on raw material exports shall make China play an important role in the process of recovering from the recession. China’s export share exceeds 25% in the cases of Brazil, Peru, and Chile. Beijing will most certainly strive to use its economic influence for the purpose of negotiating the best possible conditions for the 5G markets, as well as greater engagement of other countries in the BRI project.

In 2019, the value of commodity exchange between China and the countries of said region exceeded USD 319 billion[43]. Investment cooperation between both parties has also been developing dynamically. From 2005 to 2017 China invested – in the form of direct investments – around USD 100-110 billion[44], with most of them going to the mining and energy sectors. In the case of Argentina, Chinese authorities played a constructive role in keeping this country financially stable through so-called ‘currency swaps’ that took place in 2018[45]. Global economic crisis makes cooperation with China even more critical for the Latin American countries.

Europe

Directions and frequency of Xi Jinping’s visits to Europe are a clear sign that Western European countries – particularly France, Germany, Great Britain, The Netherlands, and Italy – hold more importance than the rest of the continent, which is determined by a range of factors, including the attractiveness of Western Europe for China’s investments, and the fact that it is a region from which advanced technologies can be obtained. In 2019, China was the EU members’ main importer (19%) and the third-largest exporter (9%). The value of commodity exchange reached 560 billion euros (export: 362 billion, import: 198 billion), with the EU deficit valued at 164 billion euros[46].

Relations with France and Germany are of the utmost significance for China, simply because these are the countries that play the most important role in the functioning and development of the EU. Beijing’s approach towards Europe can be regarded as minilateralism, which is based on the idea of selecting a narrow group of states with the proportionally greatest influence over the situation in the region and shaping the relations within the EU. The importance of the axis Berlin-Paris has increased since Great Britain left the EU, which shall make it for Beijing even more crucial to maintain a good relationship with said countries. Newer members of the EU – the countries that joined after 2004 – play rather a smaller part in China’s economic policy, which is demonstrated by a very low level of direct investments[47].

The establishment of the ‘16+1’ format (from 2019 onwards ‘17+1’) for Central and Eastern Europen (CEE) countries in 2012 was supposed to stimulate cooperation with China, but instead it mainly brought disappointments and an increase in the trade deficit. Except for Hungary, Serbia, and Greece, countries constituting the format have limited contacts with Beijing and their level of interdependence with the Chinese economy is much lower than in the case of Western European states.

From Beijing’s perspective, it is imperative to maintain the EU’s ambiguous position towards the confrontation between China and the US, and to put a strong emphasis on its economic cooperation with the EU. The PRC will seek to use the access to its own market as the main argument for maintaining lively cooperation, in spite of the more and more frequent human rights violations in China and the global confrontation between China and the US. Transnational corporations, particularly German automobile and telecommunication companies, will be amongst the key actors shaping the EU policy. The EU’s priority remains the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, which aims at guaranteeing a “level playing field” and “reciprocity” in the treatment of European companies.

Middle East

In the last decade, China’s growing demand for natural resources and the pursuit of infrastructure contracts have been the main drivers of Chinese diplomacy in the Middle East[48]. Oil imports from the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East account for more than 40% of the total amount of oil imported to China[49], and the value of imports from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)[50] alone exceeded USD 105 billion in 2018. These factors make the cooperation with the Arab countries of paramount importance for the energy security of the PRC. Quite significant is the economic cooperation with the countries of the Arabian Penninsula, which, according to the American Enterprise Institute, attracted as much as USD 82 billion of Chinese investments and infrastructure contracts between 2005 and 2020.

The complicated geopolitical situation in the region, related to Iran’s open rivalry with Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the USA, makes it crucial for Chinese diplomats to proceed with utmost caution. The PRC wants primarily a free implementation of the economic agenda in the region, which can be easily undermined by either regular armed conflicts and proxy wars. At the same time, China is expressing political support for Russia, which has grown to become one of the leading regional players since the beginning of the conflict in Syria. Support for the Assad regime and the blocking of resolutions relating to Syria in the UN Security Council is also based on an official attachment to respect for the principles of sovereignty and non-interference[51]. However, Chinese involvement in the Middle East is almost exclusively limited to the economic dimension, and Beijing does not seem to have the ambition to replace the USA as the main military power in the region.

In 2016, during his Middle East tour, President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Egypt, and in the case of the first two countries declarations of willingness to upgrade their relationship with China to a comprehensive strategic partnership were made[52]. Almost simultaneous visits to two rival countries are symptomatic of the PRC’s entire policy towards the Middle East. The twin-track policy that aims at maintaining good relations with Riyadh and Tehran shall foster promoting economic interests of the PRC and stability in the region. Fears of deteriorating relations with Saudi Arabia are one of the main arguments against the alleged alliance of China and Iran, which was reported in the media in July 2020[53].

Africa

Cooperation with African countries, as well as other countries of the so-called ‘third world’[54] has been regarded by Beijing as an extremely important direction of foreign policy since the ‘Mao era’. The support of post-colonial states and their acceptance of the communist idea were meant to lend credibility to the image of China as an alternative to the two empires (the US, and the USSR). Today for Beijing, Africa is primarily an area of an economic expansion and raw material acquisition. However, these activities are not devoid of a political component that is gaining in importance with the globalisation of the China-US rivalry, Chinese attempts to create a polycentric power structure, as well as the so-called Chinese “march through international institutions”.

Economic contacts have clearly gained in intensity since the beginning of the 21st century as a consequence of China’s surge in demand for raw materials and the pressure of the Chinese authorities on global expansion as part of their “exit strategy” (zou chuqu 走出去). No less important was the growing financial and organisational potential of state-owned companies, which now allows the implementation of large infrastructure projects such as the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi and Addis-Djibouti railroads, or the Mambilla power plant. In the period 2014-2018 China was the main source of investment in Africa, with USD 72.2 billion invested, ahead of the US (USD 30.85 billion), and France (USD 34.17 billion)[55]. The PRC was also the region’s largest trading partner with the trade exchange reaching USD 208 billion in 2019.

It is no coincidence that the African countries were visited by Xi Jinping soon after taking power, although their selection, except for South Africa, may at first glance be quite surprising. After the meeting with Vladimir Putin in 2013, Xi made trips to three African states – Tanzania, South Africa, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The visit that he paid to South Africa was linked to the planned BRICS summit and, it is important to emphasise, this country remains China’s main economic partner in Africa. The trip to Tanzania was a result of advanced negotiations regarding the construction of a port complex in Bagayomo with an estimated value of USD 10 billion. An agreement on this matter was signed with China Merchants Port in May 2013, two months after Xi Jinping’s visit[56]. The arrival in the Democratic Republic of Congo, however, should in turn be linked to the then announced plan to build a USD 14 billion hydroelectric power plant on the Congo River with the participation of China Three Gorges[57]. Although the project has encountered numerous difficulties since then, there is still a chance for it to be implemented[58]. In 2015 Xi Jinping visited South Africa again, in order to participate in the China-Africa Forum (FOCAC), where he declared that Beijing would invest an additional USD 60 billion in Africa. The visit to Zimbabwe was accompanied by giving a loan of USD 1.2 billion for the development and modernization of the country’s largest power plant[59]. In 2018 Jinping visited four African countries (South Africa, Senegal, Rwanda, and Mauritius) in connection with the BRICS summit that was held in South Africa, and the promotion of the New Silk Road projects.

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated new challenges for China’s relations with Africa, but at the same time, Beijing will seek to use economic and political tools to strengthen its influence and improve its image through the Belt and Trail Initiative. During the virtual FOCAC summit in June 2020, President Xi announced debt cancellation for some countries and providing a Covid-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available[60. The difficult economic situation will accommodate tightening of the relationship between African states and China, without whom recovering from the crisis will be extremely difficult. African states will possibly be quite valuable partners for China within the international organisations, where tensions with Western countries are increasing in frequency. The postcolonial history of the continent, along with the lack of alliances with the US, shall additionally benefit the relationship between China and African states.

*Maps presented in this analysis were prepared by Natalia Matiaszczyk, an intern at the Institute of New Europe, for which we would like to express our gratitude.

[1]China’s Peaceful Development, Information Office of the State Council The People’s Republic of China September 2011, Beijing; 中国捍卫核心利益的决心坚定不移, 人民日报, 2019年05月09日 01 版.

[2] Angela Poh & Mingjiang Li, A China in Transition: The Rhetoric and Substance of Chinese Foreign Policy under Xi Jinping, Asian Security, 13:2, 2017, 84-97, DOI: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1286163; Yan Xuetong, From Keeping a Low Profile to Striving for Achievement, The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 7:2, 2014, 153–184; Weixing Hu, Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy’: The Role of Leadership in Foreign Policy Transformation, Journal of Contemporary China, 28:115, 2019, 1-14, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2018.1497904.

[3] Zhimin Lin, Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy’: The Impacts of China’s Growing Capacity, Journal of Contemporary China, 28:115, 2019, 31-46, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2018.1497909.

[4] Avery Goldstein, China’s Grand Strategy under Xi Jinping: Reassurance, Reform, and Resistance, International Security, 45:1 2020, 164-201.

[5]习近平关于实现中华民族伟大复兴的中国梦论述摘编, 中共中央文献研究室 编, 出版时间:2013年12月

[6]朱炳元, 实现“两个一百年”奋斗目标的内在逻辑, 018年03月09日.

[7]刘杨, 关于中国在南海的领土主权和海洋权益中国政府严正声明, 2016-07-12, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/12/content_5090628.htm; 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室, 钓鱼岛是中国的固有领土 2012年9月.

[8] President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries, 2013/09/07, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml.

[9] Marcin Kaczmarski, Jedwabna globalizacja: Chińska wizja ładu międzynarodowego, OSW Punkt Widzenia nr 60, Warszawa 2016.

[10] Patrycja Pendrakowska, Tydzień w Azji: Inauguracja Centrum Badań Myśli Xi Jinpinga nad Dyplomacją, Instytut Boyma, 11 sierpnia 2020, https://instytutboyma.org/pl/tydzien-w-azji-inauguracja-centrum-badan-mysli-xi-jinpinga-nad-dyplomacja/

[11] China Global Investment Tracker, American Enterprise Institute, 2020, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

[12] Paweł Paszak, Sino-Russian Partnership in the Face of Changing Balance of Power and Internal Barriers, Historia i Polityka, No. 30(37)/2019, pp. 89–106

[13] Sustaining Confidence in a World Undergoing Transformation, 18th St Petersburg International Economic Forum

[14] Mankoff, Jeffrey. “Russia’s Asia Pivot: Confrontation or Cooperation?” Asia Policy, no. 19, 2015, p. 67.

[15] James Henderson, Russia’s gas pivot to Asia: Another false dawn or ready for lift off? , Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford Energy Insight: 40, November 2018https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Russias-gas-pivot-to-Asia-Insight-40.pdf

[16] Michal Lubina, Between Reality and Dreams: Russia’s Pivot to Asia,in: Dominik Mierzejewski and Grzegorz Byawel, Building the Diverse Community: Beyond Regionalism in East Asia, “Contemporary Asian Studies Series”, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź 2016, p. 161-163.

[17] Voting Practices in the United Nations in 2018. Report to Congress Submitted Pursuant to Public Laws 101 246 and 108-447, US Department of State, 2019.

[18] Ilya Razlomalin, Ilya Sushin, The Road to China: An Opportunity for Russian Gas, Italian Institute of International Affairs, February 21 2020, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/road-china-opportunity-russian-gas-25096

[19] UN Comtrade, https://comtrade.un.org/data/

[20] Remarks By President Obama to the Australian Parliament, Parliament House Canberra, Australia, November 17, 2011, The White House, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/11/17/remarks-president-obama-australian-parliament; Hillary Clinton, America’s Pacific Century, Foreign Policy, 2011

[21] Veronica Stracqualursi, 10 times Trump attacked China and its trade relations with the US, ABC News, November 9 2017, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/10-times-trump-attacked-china-trade-relations-us/story?id=46572567

[22] UN Comtrade, https://comtrade.un.org/.

[23] US Census Bureau, Trade in Goods with China, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

[24] Review of China’s Foreign Trade in 2019, General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China, January 14, 2020. http://english.customs.gov.cn/Statics/f63ad14e-b1ac-453f-941b-429be1724e80.html

[25] ASEAN Investment Report 2019: FDI in Services: Focus on Health Care, s. 22

[26] China’s CCCC, Philippines’ Macroasia win $10 billion airport project, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cccc-philippines/chinas-cccc-philippines-macroasia-win-10-billion-airport-project-idUSKBN1YL12E

[27] Speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Indonesian Parliament, 2 October 2013, Jakarta, Indonesia, ASEAN-China Center, http://www.asean-china-center.org/english/2013-10/03/c_133062675.htm

[28] Mingjiang Li, The Belt and Road Initiative: geo-economics and Indo-Pacific security competition, International Affairs, Volume 96, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 169–187, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz240

[29] US Department of State, A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Advancing a Shared Vision, NOVEMBER 4, 2019

[30] Kai He, Mingjiang Li, Understanding the dynamics of the Indo-Pacific: US–China strategic competition, regional actors, and beyond, International Affairs, 96:1, 2020, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz242; Shicun Wu, 中国如何破解美国的“印太战略, National Institute for South China Sea Studies, 2019, http://www.nanhai.org.cn/review_c/402.html.

[31] Harsh V. Pant, The US-India-China ‘Strategic triangle’: theoretical, historical and contemporary dimensions, India Review, 18:4, 2019, 343-347, DOI: 10.1080/14736489.2019.1662192.

[32]中华人民共和国和巴基斯坦伊斯兰共和国关于深化中巴全天候战略合作伙伴关系的联合声明(全文, 2020年03月17日 .

[33] Ganeshan Wignaraja, Dinusha Panditaratne, Pabasara Kannangara and Divya Hundlani, Chinese Investment and the BRI in Sri Lanka, Chatham House, Asia-Pacific Programme, March 2020, 5.

[34] Yogesh Joshi & Anit Mukherjee, From Denial to Punishment: The Security Dilemma and Changes in India’s Military Strategy towards China, Asian Security, 15:1,2019, 25, DOI: 10.1080/14799855.2019.1539817; Christian Wagner, The Role of India and China in South Asia, Strategic Analysis, 40:4, 2013, 307-320, DOI: 10.1080/09700161.2016.1184790, 318.

[35] United Nations Comtrade Database, https://comtrade.un.org/data/.

[36] S. Pirani, Central Asian Gas: prospects for the 2020s, The Oxford Institute for energy Studies, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Central-Asian-Gas-NG-155.pdf.

[37] Temur Umarov, China Looms Large in Central Asia, Carnegie Moscow Center, March 30 2020, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/81402.

[38] Worldwide Chinese Investments & Construction (2005 – 2020), American Enterprise Institute, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

[39] Daisuke Kitade, Central Asia Undergoing a Remarkable Transformation: Belt and Road Initative and Intra Regional Cooperation, Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report August 2019.

[40] Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Shanghai, June 15, 2001, 2-3.

[41] President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries, 2013/09/07, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml.

[42] Alicja Paszak, Chińskie inwestycje bezpośrednie w Ameryce Łacińskiej, Instytut Nowej Europy, 26 marca 2020, https://ine.org.pl/chinskie-inwestycje-bezposrednie-w-ameryce-lacinskiej/.

[43] Thomas Lum, China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean, Congressional Research Service, June 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10982.pdf.

[44] Rolando Avendano, Angel Melguizo and Sean Miner, Chinese FDI in Latin America: Trends with Global Implications, Atlantic Council, June 2017, s. 1; Enrique Dussel Peters, Monitor of Chinese OFDI in Latin America and the Caribbean 2018, RED ALC-China, March 21st, 2018, 2.

[45] Eliana Raszewski and Scott Squires, UPDATE 1-Argentina expands China currency swap as Beijing eyes Latin America, Reuters, November 9 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/argentina-economy-currency/update-1-argentina-expands-china-currency-swap-as-beijing-eyes-latin-america-idUSL2N1XJ1VW.

[46] China-EU – international trade in goods statistics, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/China-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics.

[47] Agatha Kratz, Mikko Huotari, Thilo Hanemann, Rebecca Arcesati, Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update, A report by Rhodium Group (RHG) and the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), April 2020, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/MERICS-Rhodium%20Group_COFDI-Update-2020%20%282%29.pdf.

[48] Worldwide Chinese Investments & Construction (2005 – 2020), American Enterprise Institute, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

[49] The share of countries located in the Arabian Peninsula in the import of China’s oil in 2019: Saudi Arabia 16.8%, Iraq 9.9%, Oman 6.9%, Kuwait 4.5%, United Arab Emirates 3.1%.

[50] Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC).

[51] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – The time-tested guideline of China’s policy with neighbours, July 30 2014, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/t1179045.shtml.

[52] Chinese president back home after visits to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iran, People’s Daily Online, January 24 2016. http://en.people.cn/n3/2016/0124/c90883-9008539.html.

[53] Farnaz Fassihi and Steven Lee Myers, Defying U.S., China and Iran Near Trade and Military Partnership, New York Times, July 11 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/11/world/asia/china-iran-trade-military-deal.html; The Iran-China Axis, The Wall Street Journal, July 17, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-iran-china-axis-11595027021.

[54] Chairman Mao Zedong’s Theory on the Division of the Three World and the Strategy of Forming an Alliance Against an opponent, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/ziliao_665539/3602_665543/3604_665547/t18008.shtml.

[55] Payce Madden, Figure of the week: Foreign direct investment in Africa, Brookings, October 9, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/10/09/figure-of-the-week-foreign-direct-investment-in-africa/.

[56] UPDATE 1-Tanzania signs port deal with China Merchants Holdings, Reuters, May 30, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/tanzania-china-infrastructure/update-1-tanzania-signs-port-deal-with-china-merchants-holdings-idUSL5N0EB3RU20130530.

[57] Teo Kermeliotis, Will ‘world’s biggest’ hydro power project light up Africa? CNN Bussiness, June 28 2013, https://edition.cnn.com/2013/06/28/business/biggest-hydropower-grand-inga-congo/index.html.

[58] Pauline Bax, Michael Kavanagh, China Dominates Bid for Africa’s Largest Dam in New Pact, Bloomberg Green, August 7 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-07/chinese-firms-dominate-bid-to-build-congo-s-inga-dam-in-new-pact.

[59] Zimbabwe: China promises $1.2bn loan for Hwange thermal power plant upgrade, Africa’s Power Journal, December 2 2015, https://www.esi-africa.com/top-stories/zimbabwe-china-promises-1-2bn-loan-for-hwange-thermal-power-plant-upgrade/.

[60] Xi Jinping’s speech at Extraordinary China-Africa Summit on Solidarity against COVID-19, China Global Television Network (CGTN), 18 June 2020. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-06-17/Full-text-Xi-s-speech-at-China-Africa-summit-on-COVID-19-fights-Rp7hgf5tu0/index.html.

IF YOU VALUE INE’S WORK, BECOME ONE OF ITS DONORS!

Funds received will be used to finance further publications.

Anyone can contribute by transferring donations to INE’s bank account:

95 2530 0008 2090 1053 7214 0001

with the following payment title: „darowizna na cele statutowe”

Comments are closed.