Main points:

– The proliferation of digital communication profoundly widened the access to discourses responsible for shaping national imaginations, however, it had very little influence on making these imaginations more egalitarian and democratic.

– Nationalisms still manifest themselves in banal ways (Michael Billig) but today this means not only national flags, sport teams or the division into home and abroad news in daily newspapers, but also user-generated content such as memes.

– As analysed in the case study of a Facebook profile – Slavorum, digital banal nationalism might not have any significant political sway but can make national imaginations more bearable.

Almost 40 years after its publication, Benedict Anderson’s idea of “imagined communities” remains to be one of the most seminal works in the field of nationalism studies. While his theory still holds a lot of explanatory value, it seems that the advancements of the digital era are bringing even greater diversity to existing types of nationalisms, putting into question whether nations are what Anderson wanted them to be. After all, if “communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined” (Anderson 2006 [1983]: 5), this style is clearly very different in the internet-dominated times.

This essay argues that digitally imagined communities differ from Anderson’s conceptualisation as the modern acts of imagining nations, which are predominantly characterised by their “banality” and supposedly non-political characters. Furthermore, the agency behind the acts of imagination is located within a significantly more diverse number of actors than suggested by Anderson. The first section, reviewing the existing literature, investigates whether digital communication fulfils its promise and democratises the processes involved in imagining nations. The second section explains the importance of new, digital forms of “banal nationalism” on how communities are being imagined. In particular, one case study will be analysed in depth in the second section – memes from a Facebook profile focused on Slavic cultures – Slavorum.

Section 1. Digital communication does not make nations or nationalisms more egalitarian

Insofar as this is not a completely new phenomenon, the notion of imagined communities has been increasingly applied to numerous new contexts that are not necessarily related to nations. The theory is used to the extent that one can even read about imagined communities of football fans (Levental et al. 2016). Frequently, the adjective ‘digital’ is also added to signify that the shaping of community bonds now happens through digital means. However, a large number of unrelated communication practices are often referred to with this umbrella term. All of this might suggest that Anderson’s theory is simply too broad to explain the peculiarities of national communities. As pointed out by many critics, creating imagined connections to arbitrary groups “is true as much for religious communities as it is for employees of large corporations or members of far-flung social and political movements” (Schneider 2018: 36). While this is not a new criticism, this problem seems to be greatly exacerbated by the increased connectivity of the digital era that allows us to make connections that used to be inconceivable. Emphasising the salience of mass communication, Anderson believed that nations are imagined largely through communication practices (2006 [1983]: 35). It is these practices that not only call nations into being but also influence their character – what are the ins and outs criteria, elements of identity or crucial national symbols. As such, it is only natural that there is a growing number of attempts to reconceptualise nationalism in general and challenge his ideas in particular. One of the most recurring features of such reconceptualisation is highlighting greater pluralism, whereby “citizens can express opinions and deliberate public affairs despite state constraints” (Rongbin 2018: 184). This, it is claimed, should democratise the process of imagining a nation and, as a result, create symbols or important identity elements more egalitarian or representative of all layers of a given society (Mihejl and Jimenez-Martinez 2020: 3). However, this account is too often marked by a naive optimism insensitive to asymmetries of power that are also present in the internet sphere. The recent phenomena such as “territorialization of the internet” make us acutely aware that “a network that once seemed to effortlessly defy regulation is being relentlessly, and often ruthlessly, domesticated” (Kapur 2019). This should not come as a surprise if we realise that “technology is neither good or bad, nor is it neutral” (Kranzberg in Pariser 2012: 2342). We should be attentive to “design choices, the structural features of the political economy, and human psychology” that cannot be disconnected from the processes of the internet communication that are responsible for imagining a nation (Schneider 2018: 56). Having taken that perspective, it is easier to see that creating imagined communities through digital means could be more about liberalisation than democratisation (Zheng 2008). In other words, the access to discourses responsible for shaping the image of a given nation is indeed much greater than in the times when it was mainly gatekeeped by newspapers or novels written by privileged elites. But it is not visibly more egalitarian. There are two main reasons as to why the internet-driven imagination of nations might have little effect on making nationalisms more egalitarian.

Firstly, it should be clear that the internet discourses enhance interest articulation. Lutz and Toit, in their analysis of social movements argue that, devoid of any significant gatekeepers, internet users are enabled to express their opinions freely and engage in numerous networks of people at the same time, which can “lead to the repeated creation of new imagined communities of the most ephemeral kind” (2014: 96). It is unlikely that a global mobilisation of the magnitude of the Occupy movement would have been possible if not for the internet networks that allowed people to “engage in self-reflection and to nurture self-awareness” (Lutz and Toit 2014: 99). Insofar as one can conceive of a ‘from below’, global movements responsive to people’s interests coming to fruition without the internet (see Katsiaficas 1987 for an account of the long 1968 revolt), the movement would not have been an imagined community of the kind described by Anderson. For imagined communities are characterised by membership reliant on accessing “public goods” – various symbols or behaviours that one can easily identify with (Lutz and Toit 2014: 100). Given these goods need to be widely accessible, it is the internet that facilitates the creation of such imagined communities. While the internet might facilitate a relatively unfettered flow of ideas, allowing people to imagine a different kind of community, this imagination is as fleeting as the next step – aggregating these imaginations – and it is entirely reliant on other actors such as politicians or military leaders that might or might not be sensitive to these expressions. This creates a situation where the same sort of power asymmetries that we know from the ‘analogue world’ play a significant role. As such, one cannot expect digitally imagined nations and their nationalisms to be more egalitarian as “the internet economy has turned out to be much like the old economy, with a small number of mega-firms dominating the sector, relentlessly squeezing out new entrants” (Lutz and Toit 2014: 118).

Secondly, the dynamics involved in the creation of global social movements are simply different. It needs to be recognised that states or other actors such as political parties might have neither means nor a vested interest in counteracting how a specific global movement is being imagined, but this is not the case when it comes to nations and nationalisms (Kapur 2019). In fact, states frequently turn out to be these ‘mega-firms dominating the sector’. This is visibly manifested in the case of Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands described by Florian Schneider in his analysis of China’s digital nationalism. Although the islands are disputed and, as a result, uninhabited, the internet weather or travel services in China return searches relating to these islands. This “banal bias” is obviously a result of a massive power yielded by the Chinese government officials over the country’s internet providers (Schneider 2018: 76). The engagement of the Chinese state in these seemingly insignificant elements of the internet sphere should not be surprising as nationalism “must be reproduced in a banally mundane way, for the world of nations is the everyday world, the familiar terrain of contemporary times” (Billig 1995: 6). This case is illustrative of the greater predicament at stake. One cannot truly claim that the internet allows average citizens to impact the character of their imagined communities if this impact might be visible only when governments allow it or remain ambivalent. This holds particularly true in authoritarian states. Furthermore, powerful political actors have a plethora of ways to hijack discourses responsible for creating nationalisms. A visible manifestation of this could be witnessed in India where specific elements of Indian identity – being technologically-savvy or entrepreneurial – are entirely manufactured in Narendra Modi’s electoral campaigns (Rao 2018). Given disproportionate resources available to politicians, this effectively renders these discourses utterly undemocratic.

As such, it might be concluded that Partha Chatterjee’s influential critique of Anderson holds true more than ever. Asking ‘whose imagined communities’, Chatterjee points out that the influence of colonialism extends to how former colonial subjects imagine their communities and their future: “the only true subjects of history, have thought out on our behalf not only the script of colonial enlightenment and exploitation, but also that of our anticolonial resistance and postcolonial misery. Even our imaginations must remain forever colonized.” (1993: 5). This critique might be extended way beyond colonial contexts. In political discourses shaping nationalisms – regardless of where these take place – the most powerful yield significantly more influence than average citizens. This is even manifested by methodologies used in the research within the field where opinion leaders are frequently used as proxies to investigate the character of analysed discourses (Zhang et al. 2018). It is unreasonable to expect that digitally imagined communities of nations are anymore democratic or egalitarian.

Section 2. Digital “banal nationalism”

While the above discussion should suffice to prove that political imagination in the digital area is equally vulnerable to power asymmetries as it is the case in the ‘analogue world’, the possible reason for this might be that the focus of most studies is constrained to traditional forms of communication. As shown in the study of nationalism in Chinese social media, most of the opinion leaders are people influential outside of the online sphere as well (Zhang et al. 2018: 765). This excludes a huge area of internet activity where traditional opinion leaders (celebrities, politicians, journalists etc.) do not have significant power. While most of such discourses are not very political in nature, their salience should not be underappreciated. Billig writes that “daily, the nation is indicated, or ‘flagged’, in the lives of its citizenry. Nationalism far from being an intermittent mood in established nations, is the endemic condition” (1995: 7). In this light, it is problematic that “existing literature in this area employs mostly a qualitative approach, focusing on dramatic cases involving public grievances against government officials of nationalistic mobilization online” (Hyun and Kim 2015: 767). Moreover, the very character of the internet warrants a different perspective focused more on the manifestations of banal nationalism unrelated to the elites as “the production of internet content is much more decentred, diversified and pluralized than the production of traditional media content, banal reproductions of nationalism can no longer be seen simply as a top-down phenomenon” (Szulc 2017: 70). Agreeing with Bilig, it is the argument of this essay that, in the modern digital realm, this banality is no longer only manifested through state-controlled flags hanging outside the public offices or national sport teams but also in memes or viral videos generated by average internet users. These are, equally as the ‘old’ symbols, mundane but not benign manifestations of nationalism responsible for how we imagine our communities. The existing literature has an abundance of examples of new digital forms of banal nationalism such as the hidden premises suggesting citizenship needs to be connected to nationality as in the discussions on giving Turkish citizenship to Syrian refugees (Bozdag 2020: 723). Nonetheless, this notion has not been frequently deployed in the analyses of seemingly non-political internet expressions such as memes or viral videos. Potentially, the notable exception is the analysis of the memetic culture in India by Sangeet Kumar. However, this novel intervention investigates mostly memes created in the context of the heated political election of 2014. As such, the purpose behind the discussed material, as well as its deployment, makes it easy to interpret it within a pre-existing political framework rather than observing it as a manifestation of mundane internet discourse. To prove the importance of such ‘banal’ expressions for the creation of national imagined communities, it might be illuminating to look further into a specific case study of the facebook profile Slavorum.

Slavorum – banal nationalisms making national belonging more bearable

Slavorum is, by far, the most popular Facebook profile about Slavic cultures with over 1 million followers. Crucially, the profile is also characterised by an extremely active fan base with almost 0.5 million of the fans engaging with some of the profile’s content in January 2021. In addition to their activity on Facebook, they also now have accounts on other social media (Instagram, Twitter), a traditional website and an internet shop. In their own words, their internet presence is focused on creating “multimedia content in the service of empowering people to navigate the complexities of an increasingly diverse and connected world” (Slavorum 2020). While the website features some more traditional news reporting on events in Slavic countries, most of the content created in all Slavorum-branded media has a humorous overtone and consists mostly of internet memes and viral videos self-reflecting on the vices, personal traits and identity elements typically or stereotypically associated with various Slavic nations. Some of the memes make reference to the whole Slavic community of nations but many of them put some specific nations in focus. There are two distinct aspects of the memetic culture demonstrated by Slavorum. Firstly, how Slavorum is full of manifestations of banalnationalism. Secondly, how these manifestations, while reproducing the existing imagined communities of Slavic nations, differ from the mainstream discourses defining what it means to be Polish, Russian, Serbian etc.

Firstly, Slavorum’s memes might be located in a very specific geography of the internet. Insofar as this outlet is “focused on international audiences”, a large part of the published content might be hard to comprehend for outsiders or people that did not come into contact with Slavic culture. Many of the featured memes intertwine English with Slavic words (“pierogi” in Figure 1) and cultural tropes such as colourful headscarves traditionally worn by elderly Slavic women (Figure 1). Others make implicit connections to lived experiences of citizens inhabiting post-communist spaces frequently characterised by ‘messy’, badly-planned urban areas (Figure 2 and 3). This demonstrates that while “the Internet is suited to cross-national large-scale meme distribution” (Shifman 2014: 151), it is not always the case and a large part of Slavorum’s memes take for granted the cultural capital required to understand and laugh in a similar way as newspapers’ ‘home’ sections do when they report ‘national’ news.

Figure 1 (“pierogi” is a traditional Slavic dumpling dish)

Figure 2 (captioned with “Cyberpunk 2077 in Russia”, the meme makes connections to messy design of urban residential areas)

Figure 3 (this irrational design of elevator buttons is a well-known picture in many post-communist urban residential areas where neighbourhood relations are often complicated by precarious economic conditions and bad bureaucracy making some apartments permanently uninhabited)

Seen in this light, the discussed memes are not different from ‘national jokes’ analysed by Andy Medhurst. In his analysis of the English sense of humour and its influence on the conceptions of the English-ness, he points out that jokes are “explicit in the way they draw lines between those who belong and those who do not, the lines which are essential to any comic utterance or event” (2007: 191). This function of humour should be seen as creating and reproducing criteria of national belonging. Slavorum’s memes are rather brutal in this regard. Even living in Poland, Russia or any other Slavic country might not suffice as a large number of memes do not build on lived experiences of any given inhabitant of these countries. They very specifically make references to uneasy histories of these nations (usually, in connection to communist and post-communist eras) that might not be readily visible for people that were not raised in these specific cultural contexts. In other words, a millennial born to an immigrant family in Russia is unlikely to understand the memes requiring a deep knowledge of the daily life experiences of the USSR as these are often passed on only in familial contexts. Interestingly, the ins and outs criteria of national (or, in some cases more general, Slavic) imagined communities featured in Slavorum’s content might be restrictive in some ways but inclusive in others and, as such, represent a novel form of banal nationalism. While the limitations of this work do not allow to conduct any quantitative analysis of the profile’s audience, there is a lot to suggest that the demographic actively following Slavorum is not particularly nationalistic. For instance, the content referring to contentious historical events such as the Yugoslav Wars rarely causes any heated discussions. One of the memes joking about the territorial aspirations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Figure 3) was met with many comments featuring jokes about other nations’. The two most popular comments refer to the precarious economic situation of Bulgaria and the overall complicated position of the Balkan nations.

Figure 3 (all comments anonymised)

Furthermore, the users’ engagement with non-humorous types of content (news reports or feature articles) could suggest that many users lack nationalistic dispositions as they frequently display the willingness to critically learn about their own and other Slavic cultures. All of the above warrant investigating whether Slavorum’s banal nationalisms extend their reach to people that might not actively identify with their national communities in other contexts. Similar suggestions have been made in regards to the memetic culture of India where it is argued that “fun relates to the spread of the Hindu nationalist ‘common sense’” (Udupa 2019: 3145). However, this needs to be explored in further research.

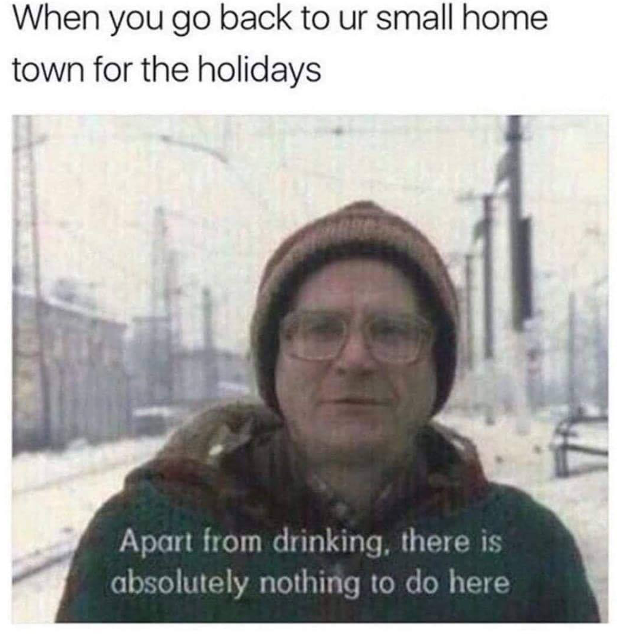

Secondly, banal nationalisms present in Slavorum’s content are peculiar as they frequently pose a challenge to the dominant discourses creating national imagined communities. Overwhelming majority of Slavorum’s memes represent a self-ridiculing type of humour (Gordon 2010). A huge number of memes make fun of the economic conditions of the Slavic countries (Figure 4), traditional religiosity (Figure 5) or prevalent alcoholism (Figure 6). In other contexts, this type of humour has been shown to be an interesting tool to challenge the dominant notions of nationhood, as in the case of India where one of the memes’ creators said that his “version of the truth is only slightly madder than what the nationalists actually believe” (Udupa 2019: 3159). It is unclear whether Slavorum’s creators emphasise Slavic vices or political absurdities in order to challenge them. Given the lack of explicitly political character, it is unlikely. Nonetheless, it does not necessitate that such memes might not undermine and contest the dominant images of discussed nations.

Figure 4

Figure 5 (the meme references the tradition of displaying religious symbols in bedrooms)

Figure 6

Clearly, it is impossible to propose a definitive account of how Slavic nations are imagined. But it seems self-explanatory that no state-sponsored nationalism would emphasise national vices or point out the absurdities created by the economic situation as it clearly goes against their vested interest of legitimising their rule. Furthermore, far-right nationalistic parties in Eastern Europe are also cautious in regards to their membership in the so-called Western world, and their criticism of the European Union or Western countries remain congruent with economic aspirations of belonging to the Western world (Bustikova 2017). This is the opposite of what might be observed in a large number of Slavorum’s memes revealing the shameful economic absurdities of the lived experiences of Slavic nations that fall short of the “Western world standards”. The contrasts between the discussed manifestations of digital banal nationalisms and its more mainstream versions do not necessarily suggest they incentivise contesting the status quo as “even when the existing system does not accommodate their self or group interest, people rationalize this dissonance by employing stereotypes naturalizing their disadvantageous positions and accepting illegitimate explanations justifying the status quo” (Hyun and Kim 2015: 769). Given a large part of Slavorum’s memes build on stereotypical images of Slavic nations, this seems to be an apt explanation of the digital imagined communities forged through the analysed content. A similar account is being proposed by Łukasz Szulc who explores the manifestations of banal nationalism in LGBTQ websites in Poland and Turkey. Szulc suggests that the function of intermingling national symbols with rainbow or lambda “may be not to challenge hegemonic national discourses in a public debate but to domesticate the nation, so that queers too feel minimally at home within this overarching narrative” (Szulc 2016: 318). Slavorum might be a popular social media outlet but its reach is unlikely to have any meaningful influence on public discourses responsible for how nations are imagined. In this perspective, it becomes a site that, through the use of laughter, makes it more bearable to imagine one as Czech, Russian or Macedonian.

Conclusion

The above analysis is an attempt to better understand the reality in which digitally imagined communities differ from Benedict Anderson’s account of nations. The existing debate on digital nationalism has been characterised by an abundance of overoptimistic academic research, insensitive to the contexts in which technologies are being deployed. To date, nothing suggests that moving the same discourses responsible for creating and reproducing national communities to the online sphere makes such communities distinctively different in its most mainstream manifestations. However, there is a growing body of online phenomena allowing individuals to influence their own conceptions of imagined communities to which they belong. To this end, this study took a qualitative approach to analyse Slavorum – an immensely popular profile in social media about Slavic cultures. The confines of this essay do not allow to investigate all the intricacies involved in the interactions happening within this site. As such, this is a demonstrative but not representative work that aims to suggest directions of further research in regards to the digital era’s reconceptualisation of nationalism in general and the conception of imagined communities in particular.

Bibliography

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications.

Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. London: Sage.

Bozdağ, Ç. (2019). Bottom-up nationalism and discrimination on social media: An analysis of the citizenship debate about refugees in Turkey. European Journal Of Cultural Studies, 23(5), 712-730.

Buštíková, L. (2018). The Radical Right in Eastern Europe. Oxford Handbooks Online.

Chatterjee, P. (1993). The nation and its fragments. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Gordon, M. (2010). Learning to laugh at ourselves: humor, self-transcendence, and the cultivation of moral virtues Educational Theory, 60(6), 735-749.

Han, R. (2018). Contesting cyberspace in China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hyun, K., & Kim, J. (2014). The role of new media in sustaining the status quo: online political expression, nationalism, and system support in China. Information, Communication & Society, 18(7), 766-781.

Kapur, A. (2019). The Rising Threat of Digital Nationalism. Retrieved 12 January 2021, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-rising-threat-of-digital-nationalism-11572620577

Katsiafikas, George. (1987) The Imagination of the new left: A global analysis of 1968. Chapter 1: The New Left as a World Historical Movement’,

Levental, O., Galily, Y., Yarchi, M., & Tamir, I. (2016). Imagined communities, the nline sphere, and sport: The Internet and Hapoel Tel Aviv Football Club fans as a case study. Communication And The Public, 1(3), 323-338.

Medhurst, A. (2007). A national joke. London: Routledge.

Mihelj, S., & Jiménez‐Martínez, C. (2020). Digital nationalism: Understanding the role of digital media in the rise of ‘new’ nationalism. Nations and Nationalism, 1-16.

Schneider, F. (2018). China’s digital nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pariser, E. (2012), The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (Kindle ed.). New York et al.: Penguin Books.

Zhang, Y., Liu, J., & Wen, J. (2018). Nationalism on Weibo: Towards a Multifaceted Understanding of Chinese Nationalism. The China Quarterly, 235, 758-783.

Lutz B., du Toit P. (2014) New Imagined Communities in the Digital Age in Defining Democracy In A Digital Age.

Rao, S. (2018). Making of Selfie Nationalism: Narendra Modi, the Paradigm Shift to Social Media Governance, and Crisis of Democracy. Journal Of Communication Inquiry, 42(2), 166-183.

Slavorum (2021), Figure 1. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1904550226349967

Slavorum (2021), Figure 2. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1891156007689389

Slavorum (2021), Figure 3. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1900999593371697

Slavorum (2021), Figure 4. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1833088563496134

Slavorum (2021), Figure 5. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1870213413116982

Slavorum (2021), Figure 6. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1892857830852540

Slavorum (2021), Figure 7. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Slavorum/photos/1878239832314340

Slavorum (2020). Retrieved 12 January 2021, from https://www.slavorum.org/

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in Digital Culture (MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Szulc, L. (2016). Domesticating the nation online: Banal nationalism on LGBTQ websites in Poland and Turkey. Sexualities, 19(3), 304-327.

Udupa, S. (2019): Nationalism in the Digital Age: Fun as a Metapractice of Extreme Speech. In: International Journal of Communication, Vol. 13, 3143-3163

Zhang, Yinxian, Jiajun Liu and Ji-Rong Wen. 2018. “Nationalism on Weibo: Towards a Multifaceted Understanding of Chinese Nationalism.” The China Quarterly 235, 758-83

IF YOU VALUE THE INSTITUTE OF NEW EUROPE’S WORK, BECOME ONE OF ITS DONORS!

Funds received will allow us to finance further publications.

You can contribute by making donations to INE’s bank account:

95 2530 0008 2090 1053 7214 0001

with the following payment title: „darowizna na cele statutowe”

Comments are closed.