This text is a translation of the transcription of the conversation conducted by Michal Banasiak and is the last interview conducted as part of the Polish-Czech Forum.

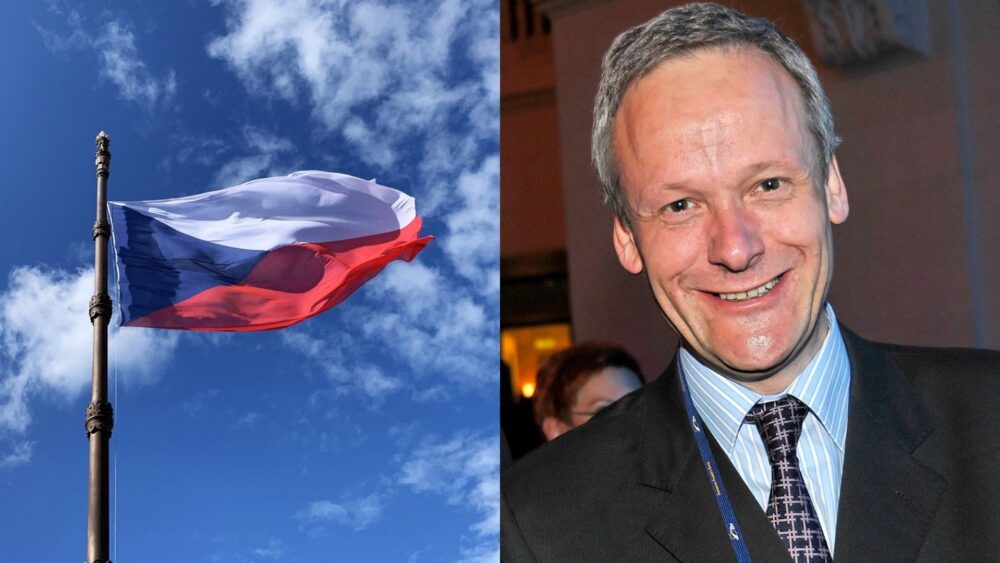

Cyril Svoboda – President of The Diplomatic Academy in Prague; Former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic.

Michał Banasiak: Hello and welcome. My name is Michał Banasiak, and this is the Institute of New Europe in a series of talks within the Polish-Czech Forum Project. Our guest today is Mr. Cyril Svoboda, director of Diplomatic Academy in Prague, former Deputy Prime Minister, and former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechia. Good morning.

Cyril Svoboda: Good morning. Thank you so much for inviting me. Thank you.

Michał Banasiak: Thank you for being with us. I would like to start our meeting with a short journey to the past, to the time when you were the Deputy Prime Minister of Czechia and also the Minister of Foreign Affairs. It was in the time when Czechia was in the process of joining the European Union, as well as Poland and other countries from the region. How would you evaluate this period, almost 20 years of EU membership for Czechia, Poland, and countries in our region?

Cyril Svoboda: It was an exciting time when we joined the EU because it was the most robust enlargement with 10 countries joining, including your country, Poland, and my country, the Czech Republic. Since that time, a lot of things have changed, and, of course, the EU has also changed because we have faced some crises. I mean the migration crisis, later the problem with the war against Ukraine, and generally speaking, it seems to me that we, the Czech Republic and Poland, still have a lot to do in harmony, despite the fact that Poland is one of the biggest country in the EU. My country is of medium size, but we are neighbors and we share common interests, primarily now in the time of the war against Ukraine we are sticking together. I mean Poland and the Czech Republic. What is obvious? We are the line between the so-called old member states and the new ones.

Poland is a leading country among the family of so-called new ones. So that’s why I am very supportive for the cooperation between Poland and the Czech Republic because, as I said, we have a common past, I mean also the occupation of the Soviet empire. So we have been occupied by the Soviet army. But your situation has been slightly different, but still, that’s why we are neighbors and we have to do a lot in common.

Michał Banasiak: We think that our countries have properly used these almost two decades of being EU membership.

Cyril Svoboda: Yes, and we have taken a very strong lesson. One is how important it is to stick together. It’s very important. So despite the difficulties and maybe some differences and maybe despite different priorities, but generally speaking, mainly the war against Ukraine showed us how important it is to stick together. So that’s very important, and in my view, we will differ in the future, maybe in some priorities. But generally speaking, we still will have to have in our minds and our souls that if there is a crisis, the problems are to be put aside, and we have to stick together.

Michał Banasiak: And how would you compare the European Union from 2004-2003 and the current one? Because you mentioned that the European Union is changing all the time, and we, of course, are seeing it every day. So how would you compare the same organization but from two periods? And, of course, I’m not asking for the size of the European Union because now it’s much bigger than 20 years ago, but the political meaning of it.

Cyril Svoboda: Yes, in my view, there are three differences. Three. The first one is that in the past, the Member States sent to the EU maybe politicians and people of the best quality. I’m sorry, but it seems to me that today those who are in the European Commission or some other institutions are not the best ones. We are in a time of crisis; we have taken lessons from COVID and other very difficult times. The reason is that we have to be very careful, very careful after the elections to the European Union about what type of people are to be chosen and nominated for composing the New Commission and other important positions. You know, Joseph Borrell and other persons… So I am sorry, but in my view, it is not the best European quality. That’s one lesson.

The second is that the process of liberalization is still marching on. And of course, that’s obvious that this is a process in this society. I’m not following the line of the process, but this item is also a political dividing line in EU. We now have more conservative countries and maybe some less conservative countries, and maybe this is also the momentum that is to be taken together.

The last lesson is that Europe has to be strong enough to protect European interests, maybe alone, not being supported by the United States or some other powers.

The last one is that the United States is interested in Europe, of course, the one in Ukraine is a good example, but still, we don’t know who will be elected in the coming presidential elections. The last lesson is that Europe has to be strong enough to protect European interests, maybe alone, not being supported by the United States or some other powers.

Michał Banasiak: We have some pan-European challenges now, for instance, the ongoing war in Ukraine, the energy crisis, migration. Do you believe it is possible to find solutions for those challenges at the European Union level, or is it not possible because different countries have different priorities? For instance, we see Hungary and its politics, directs to Russia, which is totally different than, for instance, Poland or Czechia.

Cyril Svoboda: Yeah, you are absolutely right. So that’s why I am still stressing that we have to find good people, very qualified and experienced people, for the European institutions because there are some differences. But if there’s a deep European crisis, we have to stick together because if there’s a crack, it will be easy for Russia or China or some other big countries to destroy, affect the power of the European Union. So that’s very important to listen carefully. Every single country will differ in some priorities, but the substance is to see Europe as a concept which is profitable for all of us. So again, it is a problem of people. It is not a problem of the institutions.

Michał Banasiak: We are talking about Russia and the ongoing war. I guess you agree that diplomacy failed one and a half year ago, and do you believe it can be solucion, I mean, the diplomatic way. I’m asking you, as a former diplomat and also as a director of the Academic Diplomatic Academy in Prague. Do you believe that diplomacy still can be a useful tool while negotiating with Russia? Or the only argument that Russia understands now is military power.

Cyril Svoboda: In the very end, we will need diplomacy. I don’t know if it is the right time now because we have to support Ukraine, because Ukraine defenses its own country against Russian aggression. But every single war in the course of history ended in three possible ways. One is one country defeats other country. So that’s one solution.

In my view, it is impossible in this war. Russia is not capable of defeating Ukraine, definitely not, and Ukraine is not capable of defeating Russia. Russia is not ready to sign any capitulation. The second option is a frozen conflict. A frozen conflict is for Ukraine, in my view, the worst solution because the war still continues, still does exist and Ukraine has no stable border. It will be very difficult for Ukraine in the process of joining European institutions and European integration process.

The very last one is some peace agreement. But when is the right time, it is up to the Ukrainians. So in the very end, we will need very strong diplomacy because I believe that we need some type of so-called peace agreement, despite all the arguments against Russia that Russia could break any commitments, even if they are incorporated in legally binding texts. But we will, in the very end, need some type of diplomacy.

Michał Banasiak: Do you believe that Ukraine, Moldova, Western Balkan countries can join the European Union in, let’s say, a perspective of 5-10 years? Or are there other rhetoric and diplomatic gestures for those countries that we want to negotiate with them? We want to start the process of joining, incorporating them the European Union, but it’s still too hard for them to be part of the EU in, let’s say, 5-10 years, but we should still use this political tool to make them closer to the West than, for instance, Russia.

Cyril Svoboda: Yes, there’s a crucial problem. In my view we have to negotiate, but I’m very, very sceptical about joining the EU, mainly for Ukraine. And the example with the question of grain export and Poland is a good example. It is not just a question of politics, but every single country is to meet so-called Copenhagen criteria, and it is very challenging question for Ukraine. The question of security and the borders, etc. So in my view, we have to say openly that the process will be extremely long. Not 5 or 10 years, maybe 15, maybe 20. I don’t know, but I think it is correct to tell the Ukrainians that the process is to be started, but it will take a very long time.

Michał Banasiak: What about Moldova and Serbia?

Cyril Svoboda: Serbia is under the influence of Russia. I’m very sceptical that Serbia de facto wants to join the EU. Serbia, I think, wants to take all the advantages linked with the process of accession. But in my view, Serbia is under the very strong influence of Russia. Maybe I’m wrong, but there’s a problem. But it would not be correct for Ukraine to say to some other countries, Moldova, some other countries, “You are welcome,” and for Ukraine, maybe I’m wrong, but in my view it will take too much time from the accession countries’ perspective. But we have to be correct.

Generally speaking, we have very good relations. Maybe there is a problem with the case of Turów, but that’s just one example.

Michał Banasiak: Would you agree that cooperation on the European level is now so hard because the political fights within the Member countries are so fierce, maybe more fierce than ever?

Cyril Svoboda: You know, because we have maybe double or triple problems. I mean the green deal, security, migration. So there’s a basket of problems. And it is obvious that we have to solve all of them. At the very same time, every single government, including the Polish one and the Czech one, wants to be reelected. So, of course, all the parties also have to follow the meaning the priorities in their countries. So this is a huge basket of problems, but still, the process is marching on. So that’s why I am devoted to the integration process. But I could imagine that some problems will be very difficult and will need a lot of time to be solved.

Michał Banasiak: And are you among those who think that the European Union should take more and more responsibilities on its shoulders, or do you think that rather the Member countries should decide on their own in as many areas as possible?

Cyril Svoboda: Yes, I am against deeper integration. I am against deeper integration, saying so. We have to introduce deeper integration, not in every case, but if we take seriously the competencies which are on the EU level, in my view, they have to be solved at that level. In very strong energy and other powers are in the hands of the national states to discuss and now to open the debate on how to shift the powers, competences from EU to the Member States, or vice versa. It could be very dangerous, very challenging, and very complicated because we are 27 countries. It is not just the Polish or Czech perspective we have to take into consideration, but also the perspectives of Spain, Portugal, and Finland. Because it is a huge mistake just to perceive the EU only from our perspective.

Michał Banasiak: Czechia is, as well as Poland, is among those countries that have not adopted the euro as currency so far. Is there any debate about adopting the euro in Czechia right now?

Cyril Svoboda: No, unfortunately not. Maybe I do represent the minority in my country, but I am devoted to the eurozone, not because of Europe. It’s a problem; we can handle it. I couldn’t imagine some economic problems, but politically, the eurozone represents a so-called qualified majority. If the eurozone decides something, we have just to salute and say yes, we will follow the will of the eurozone. Slovakia and some other countries, even smaller countries like Croatia and the Baltic States, they are at the table when the decision is taken. The good example is Poland and Slovakia, the only party, I am stressing, the only party it was Kotleba’s party which wanted to leave the eurozone, is not capable of crossing 5% and is out of the Parliament. Every single party even in Slovakia, Slovakia is smaller than Poland and the Czech Republic, every single party is saying yes, we have to stay in the eurozone because of being at the table when decision process is going on. So my country and Poland we have to follow the decision of eurozone.

Michał Banasiak: You said that you are representing properly minority. So why Czech community and, I guess, also politicans are against joining the eurozone. I’m curious about that because we from time to time have this debate in Poland as well.

Cyril Svoboda: You know, we were well prepared for joining the eurozone with Slovakia, but the government was in the hands of the Eurosceptic party or civil democratic party. So the Czech government decided not to join, and since that time sometimes the question is put on the table. But that’s the meaning of the society, in my view, having had very long experience, if there are some strong politicians who are saying no, there are many benefits to joining the eurozone. Of course, there are some costs we have to pay, but generally speaking, we will be in the hard court of decision making. So I think that the meaning could be changed, but you need some charismatic leading people saying yes, we on. But the Czech political elite, including the Prime Minister and some in the government, they are saying yes, we will join the eurozone when it is profitable for my country, and my answer is when? Today or tomorrow? What will happen next year? So it is a political decision to be or not to be in the zone. So when the right day is to come, I don’t know the right day. My answer is tomorrow is the right day.

It was a huge mistake to depend on Russian delivery, nearly 100%. So we are in the process of diversification, but who knows what will happen in Algeria or Qatar or some other countries because they are also, in certain ways, unstable states.

Michał Banasiak: I would like to ask about the Czech ideas on energy transformation because Czechia was among those countries that were very much dependent on Russian resources. How does the situation look now, and what are the plans for the coming years in that area?

Cyril Svoboda: That’s a good lesson we have to take from your country, because Poland is a good example of being very prepared for the diversification of energy sources. It was a huge mistake to depend on Russian delivery, nearly 100%. So we are in the process of diversification, but who knows what will happen in Algeria or Qatar or some other countries because they are also, in certain ways, unstable states. So my proposition, I’m still repeating it on Czech TV and elsewhere, is to make a huge diversification but not to close any pipeline. Ukraine is now still dependent on Russian gas. What will happen within 10 or 15 years? We don’t know. We see the situation in Algeria; Bouteflika was the president, it was a stable state, he was put aside, forced to resign, he died and now a group of generals are now leading Algieria. Who knows what will happen tomorrow? So we will have to diversify the resources as much as possible.

Michał Banasiak: I would like you to briefly sum up. I started with the European Union, but now I would like to ask you to briefly sum up the bilateral cooperation between Poland and Czechia in the last 20 years. Partly you were responsible for building them, partly not. How would you briefly sum them up and what do you think can still be developed, can still be done better, can still stick our countries together, as you mentioned in the meantime?

Cyril Svoboda: Generally speaking, we have very good relations. Maybe there is a problem with the case of Turów, but that’s just one example. I have met some very nice Polish politicians. For example, the former foreign minister, Rotfeld, and some others are very capable and very cooperative. Between us, there are some differences. Maybe Poland is more conservative than Czech Republic, which is very liberal. But we are Slavs, and there’s also a lot of common history. We do understand each other when we speak slowly. So it would be a huge mistake not to concentrate on improving relations with Poland. Poland is also very important for us, because Poland is a big country in the European Union and plays a very important role in NATO.

I am not in the fun club of the Tree Seas Project, because it might be too much even to invite the countries from the Balkans. So, in my view, it’s not a very realistic plan, but under the umbrella of NATO, we have to consult, and if there is a chance to harmonize the position, to do that.

Michał Banasiak: And what about the, for instance, connectivity? This year, it was kind of a boom in the touristic meaning. Many Czech people decided to go to Poland, instead of, for instance, Croatia, which became much more expensive than in the past. So do you think that maybe in the real connectivity, there is a place to improve?

Cyril Svoboda: Yes, of course. Many Czechs are visiting Poland, and even your prices are better, the accommodation, and many people are now realizing that the Baltic Sea is a nice sea. The Poles are very friendly, and it’s nice to spend holidays in the north of Europe. We have to support this connectivity, because traditional holidays in Croatia are, I think, overcrowded and maybe old-fashioned, because it was in the past under the communist regime, so it was for us the only chance to spend holidays at the sea in the former Yugoslavia. But yes, I do support very much and from the bottom of my heart the connectivity and the interaction between the Czechs and Poles.

Michał Banasiak: Thank you very much. The guest of the Institute of New Europe, Mr. Cyril Svoboda, director of the Diplomatic Academy in Prague, former Deputy Prime Minister and former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechia.

Cyril Svoboda:: Thank you so much for the invitation. I wish you all the best, and maybe we’ll meet in the future. Thank you. All the best.

The project “Intensifying Polish-Czech cooperation on the foreign policy priorities of both countries in 2023” aims to create a substantive basis for intensifying Polish-Czech cooperation in the field of foreign policy priorities of both countries. Public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Polish-Czech Forum 2023”. The cost of the project and the amount of grant is PLN 55 000,00.

Comments are closed.