‟When we invest in the fight against climate change, we invest in our own security.” — Federica Mogherini,[1] June 22, 2018.[2]

Key points:

– More and more evidence point to the serious implications of climate change for peace and security. Although non-climate factors continue to have a dominant influence on armed conflict, climate change itself is exacerbating such trends and tensions. In this regard, climate change acts as a risk multiplier for the outbreak of armed conflict.

– The main threats arising from climate change that affect the risk of outbreak of armed conflict include, among others, limited access to natural resources, migration, political instability and radicalization, sense of injustice and distrust of international structures.

– The role that climate change plays in international peace and security should not be underestimated. The wars in Darfur, Mali, the Central African Republic or Nigeria are examples of conflicts in which the environmental factor has played an important role.

Introduction

The warming of the climate system is indisputable. The climate changes observed over the past half century ‟are unprecedented over many decades or even millennia”.[3] Ocean temperatures have risen, snow and ice masses have declined, sea levels have risen, and the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. The ongoing warming from the pre-industrial period to the present, as a result of anthropogenic emissions, will continue and will result in long-term changes in the climate system.[4]

Experts leave no doubt about the impact of climate change will have not only on ecosystems, but also on societies and national economies. Especially the societies of the so-called “Global South” and those with limited adaptive capacity will be most affected by the effects of climate change.[5] With the recognition of how serious the security implications will be, researchers and policymakers are increasingly concerned that the effects of climate change may also increase the risk of armed conflict.

This article aims to synthesize the links between climate-related environmental change, security, and armed conflict.

Climate change as a security threat

Over the past half-century, the scope of security studies has expanded significantly along nontraditional dimensions, other than military-nuclear. The first listings of environmental threats appeared in publications and reports from the 1970s, but it was the year 1988 that initiated the securitization steps. In fact, at that time, the UN General Assembly passed the first climate protection resolution, and at the Toronto Conference, the effects of climate change were compared to the consequences of nuclear war.[6]

Once considered a problem with merely environmental implications, nowadays climate change is increasingly and boldly included as part of national and international security agendas. Commitment to addressing the causes and effects of climate change is an increasingly important part of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as for the European Union structures.[7]

Correlations between climate change and armed conflict

The assertion that environmental degradation can constitute a factor influencing armed conflict is not new. Thomas Malthus analyzed the implications of rapid population growth for food production and its scarcity as early as 200 years ago.[8] In subsequent decades, environmental problems as a catalyst for armed conflict were described by Richard Ullman and Norman Myers, as well as Robert Kaplan.[9]

According to a 2019 study by Stanford University researchers,[10] which included a group of 11 of the most experienced experts on climate and conflict, the effects of climate change combined with additional factors (such as rapid growth of population and low levels of socioeconomic development) can lead to an escalation of tensions and increase the likelihood of wars, both internal and between states. In their opinion, the risk of armed conflict increases with climate change and rising global temperatures. Nevertheless, the majority of researchers agree there are other non-climatic factors such as low levels of socio-economic development or institutional capacity that still have a much greater impact on conflict.[11] In other words, climate change should be seen as a threat multiplier and as a factor that increases the risk of armed conflict by exacerbating already existing social, economic, and environmental problems, putting a significant strain on states’ response capabilities and institutional capacity.[12] Experts estimate that climate change has so far affected 3-20% of the risk of armed conflict.[13]

(Source: own elaboration based on K. J. Mach et al., “Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict”, Nature 571 (2019), 195.)

According to the study, the risk of armed conflict will increase as temperatures rise and global warming worsens. In a scenario where temperatures rose by 2 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels, the climate impact on the risk of armed conflict would more than double. Whereas if the temperature increased by 4 degrees Celsius, the climate impact on conflict would increase by more than five times.[14]

Types of conflicts related to climate change

The following potential types of climate change-related conflicts can be identified:

– conflicts related to scarce natural resources

Shortages of particular resources taking the form of ecological scarcity – e.g. reduction in arable land, water scarcity, declining food resources (including fish stocks) – can act as catalysts for conflict. Climate change will fuel conflicts over depleting resources, especially where access to those resources is politically determined.[15] The consequences will be particularly severe in areas under heavy demographic pressure.[16]

– conflicts over the loss of territory and border disputes

Major changes in land are predicted to occur in this century. The retreat of coastlines and the flooding of vast areas could lead to the disappearance of territories, including even entire countries, such as small island states. More disputes over land and sea boundaries and other territorial rights can be expected. There may be a need to amend existing rules of international law, particularly the law of the sea, for the settlement of territorial and boundary disputes.[17]

– migration-related conflicts

The number of climate migrants is predicted to rise above 140 million by 2050.[18]Migration of population can increase the risk of political instability and conflict, both in transit territories and destination countries.[19] Between 2009 and 2019, an annual average of 22 million people left their places of residence as a result of droughts, fires, extreme weather and other climatic factors. The most vulnerable region is the sub-Saharan Africa, where as many as 86 million people will be forced to relocate by 2050. Other regions particularly vulnerable to climate migration are South Asia and Latin America.[20] Many of the people relocating since 2015 as part of the so-called ‟migration crisis” come from countries that are especially affected by climate change. Climate catastrophe is increasing the intensity of existing migrations and will trigger new migration crises.[21]

– conflicts caused by increased instability and radicalization in fragile or failed states resulting from climate change

Climate change could significantly increase the instability in failed states, overburdening the already limited ability of rulers to meet the challenges they face. It is pointed out that the inability of those in power to meet the needs of the population could create frustrations, leading to tensions between ethnic or religious groups and political radicalization.[22]

– conflicts over energy resources and control over them

Many of the world’s hydrocarbon reserves are located in regions particularly vulnerable to climate catastrophe, and oil and gas producing countries face significant economic and demographic challenges as a result of climate change. Consequently, one of the greatest potential resource conflicts arises from increased competition over access and control of energy resources.[23]

– conflicts as a result of pressure on international structures

If the international community fails to confront the threats described above, the system of multilateral cooperation may be in jeopardy. The impact of climate change could fuel resentment, especially between those who bear the greatest responsibility for climate change and those most affected by it.[24]

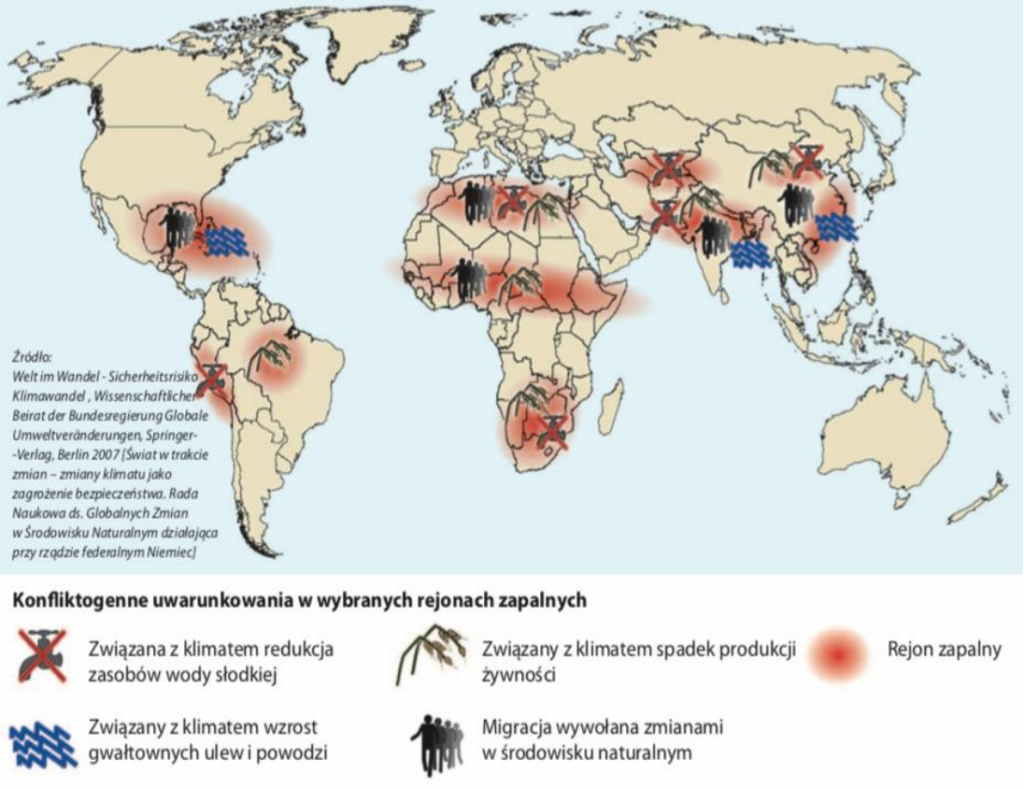

(Source: Advisory Council on Global Change, A World in Transition – Climate Change as a Security Threat. Berlin: Springer, 2007, 175.)

Examples of conflicts in which climate-related factors have played a significant role

It is worth stressing that armed conflicts that are determined by climate change are already taking place. The Darfur conflict is one of them, which in 2007 experts of UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) named the first ever conflict caused by climate change.[25] According to researchers, there is a very strong correlation between land degradation and desertification and the Darfur conflict. Adverse environmental changes had created conditions for the conflict to develop, which was further exacerbated by political and ethnic struggles.[26]

According to climatologists, climate factors have also influenced the revolution in Syria. As proven, the record-long and severe drought that blanketed Syrian territory between 2006 and 2010 and caused the mass migration of rural residents to Syrian cities was the trigger for the 2011 revolution.[27] The severity of the drought, combined with the lack of effective support for those affected by Bashar al-Assad’s government, exacerbated other tensions ranging from high unemployment to growing inequality, which together led to the outbreak of social discontent. Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that anthropogenic climate change alone did not directly spark the revolution. Instead, factors such as the long-term trend of declining rainfall and rising temperatures in the region have escalated social tensions.[28] Other examples of conflicts in which the environmental factor plays or has played a significant threat-multiplying role include those in Mali,[29] the Central African Republic, and Nigeria.[30]

Summary and recommendations

Climate change is expected to create unprecedented situations regarding security and to pose serious threats to the main pillars of peace and stability. While there is no direct evidence that climate change may be the main and only cause of armed conflicts, it certainly fuels them by exacerbating existing social, political and economic tensions.[31]

In view of the above, it is essential for the international community to take action against climate change being a real threat to security and peace:

– It is recommended that enhanced efforts should be made in order to raise awareness of climate change’s implications for security among policymakers and the general public, which at the local and regional levels would contribute to increased activity aimed at combating climate catastrophe. It is also recommended that climate change should be further integrated into states’ policies and agendas for strengthening national and international security.

– There is an urgent need to amend existing international law regarding the settlement of potential climate-related territorial and boundary disputes. Legal actions, such as the EU’s recent adoption of the European Climate Law and commitment to reach climate neutrality by 2050, should set an example for other regions.

– It is advisable to facilitate cross-border coordination and information exchange in the preparation of climate change projections as well as impact and vulnerability assessments, and to seek a common international approach to adaptation measures and responses. Global cooperation against climate change should be understood as a struggle against a common enemy.

[1] High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the European Union from 2014 to 2019.

[2] SDG, EU Event Addresses Linkages Between Climate Change and Security, http://sdg.iisd.org/news/eu-event-addresses-linkages-between-climate-change-and-security/, accessed: 20.06.2021.

[3] IPCC, Zmiana klimatu 2013,

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5-wg1-spm-3polish.pdf, 2, accessed: 20.06.2021.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Polska Akcja Humanitarna, Zmiany klimatyczne — Impas i Pespektywy, https://www.pah.org.pl/app/uploads/2017/09/2017_Zmiany_klimatyczne_impas_i_perspektywy.pdf, accessed: 20.06.2021.

[6] Do najważniejszych publikacji tego okresu należą m.in.: U Thant, Problemy ludzkiego środowiska (1969); Klub Rzymski, Limits to Growth(1972); Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons (1968).

[7] SIPRI, A Reassesment of the European Union’s Response to Climate-Related Security Risks, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/sipriinsight2102_ccr_eu.pdf, accessed: 20.06.2021; Thomas Diez, et al., The Securitisation of Climate Change: Actors, Processes and Consequences. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

[8] Thomas Malthus, The Essay on the Priciple of Population. Londyn, 1798.

[9] Zob.: Richard Ullman, Redefining Security (1983); Norman Myers, “Environment and Security”, Foreign Policy 74 (1989); Robert D. Kaplan, “The Coming Anarchy”, The Atlantic (1994).

[10] Katharine J. Mach, et al., “Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict”, Nature 571 (2019).

[11] Kamila Pronińska, „Nowe problemy bezpieczeństwa międzynarodowego: bezpieczeństwo energetyczne i ekologiczne”, w: Bezpieczeństwo Międzynarodowe, red. Roman Kuźniar et al. (Warszawa: Scholar, 2012), 325

[12] OBWE, Climate change and security, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/9/1/331901.pdf, 3, accessed 22.06.2021; Mach et al., “Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict”, 193.

[13] Ibid, 194.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Komisja Europejska, Zmiany klimatu a bezpieczeństwo międzynarodowe, http://europe-direct.kolobrzeg.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Zmiany-klimatu-a-bezpieczeństwo-narodowe.pdf, 5, accessed: 24.06.2021.

[16] Pronińska, Nowe problemy bezpieczeństwa międzynarodowego, 105-106.

[17] Komisja Europejska, Zmiany klimatu a bezpieczeństwo międzynarodowe, 6.

[18] Europejska Sieć Migracyjna, https://www.emn.gov.pl/esm/aktualnosci/15342,Prognozy-wskazuja-ze-do-roku-2050-pojawi-sie-143-mln-migrantow-klimatycznych.html, accessed: 24.06.2021.

[19] Polska Akcja Humanitarna, Zmiany klimatyczne — Impas i Perspektywy, 18.

[20] Międzynarodowy Ruch Czerwonego Krzyża i Czerwonego Półksiężyca, Responding to Disasters and Displacement in a Changing Climate Report 2020, accessed: 14.07.2021; Europejska Sieć Migracyjna https://www.emn.gov.pl/esm/aktualnosci/15342,Prognozy-wskazuja-ze-do-roku-2050-pojawi-sie-143-mln-migrantow-klimatycznych.html, accessed: 24.06.2021.

[21] Phil McKenna, Migrant Crisis, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/14092015/migrant-crisis-syria-europe-climate-change/, accessed: 14.07.2021.

[22] Komisja Europejska, Zmiany klimatu a bezpieczeństwo międzynarodowe, 7.

[23] Ibid., 8.

[24] Ibid.

[25] UNEP, Sudan, https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/disasters-conflicts/where-we-work/sudan, accessed: 26.06.2021.

[26] Beata Molo, „Bezpieczeństwo i prawa człowieka: analiza wybranych problemów globalnych”, Chorzowskie Studia Polityczne 7 (2014), 132.

[27] Colin P. Kelley, et al., “Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought”, PNAS 112 (2015), https://www.pnas.org/content/112/11/3241, accessed: 27.06.2021.

[28] Ibid.

[29] SIPRI, Climate-related security risks and peacebuilding in Mali, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/sipripp60.pdf, accessed: 28.06.2021.

[30] Międzynarodowy Komitet Czerwonego Krzyża, When rain turns to dust — report, https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/4487-when-rain-turns-dust, accessed: 27.06.2021.

[31] Molo, Bezpieczeństwo i prawa człowieka: analiza wybranych problemów globalnych, 133.

IF YOU VALUE THE INSTITUTE OF NEW EUROPE’S WORK, BECOME ONE OF ITS DONORS!

Funds received will allow us to finance further publications.

You can contribute by making donations to INE’s bank account:

95 2530 0008 2090 1053 7214 0001

with the following payment title: „darowizna na cele statutowe”

Comments are closed.